MercuryResearchers highlight problem of legacy mercury in the environment

Researchers have published evidence that significant reductions in mercury emissions will be necessary just to stabilize current levels of the toxic element in the environment. So much mercury persists in surface reservoirs (soil, air, and water) from past pollution, going back thousands of years, that it will continue to persist in the ocean and accumulate in fish for decades to centuries, they report.

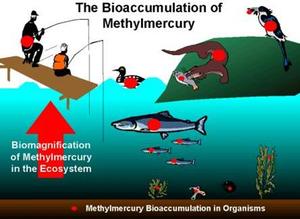

Graphic showing the path mercury follows into the human body // Source: health.state.tn.us

Environmental researchers at Harvard University have published evidence that significant reductions in mercury emissions will be necessary just to stabilize current levels of the toxic element in the environment. So much mercury persists in surface reservoirs (soil, air, and water) from past pollution, going back thousands of years, that it will continue to persist in the ocean and accumulate in fish for decades to centuries, they report. “It’s easier said than done, but we’re advocating for aggressive reductions, and sooner rather than later,” says Helen Amos, a Ph.D. candidate in Earth and Planetary Sciences at the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and lead author of the study, published in the journal Global Biochemical Cycles.

Amos is a member of the Atmospheric Chemistry Modeling Group at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), where researchers have been collecting historical data on mercury emissions as far back as 2000 BC and building new environmental models of mercury cycling that capture the interactions between the atmosphere, oceans, and land.

A Harvard University release reports that their model reveals that most of the mercury emitted to the environment ends up in the ocean within a few decades and remains there for centuries to millennia. These days, emissions are mainly from coal-fired power plants and artisanal gold mining. Thrown into the air, rained down onto lakes, absorbed into the soil, or carried by rivers, mercury eventually finds its way to the sea. In aquatic ecosystems, microbes convert it to methylmercury, the organic compound that accumulates in fish, finds its way to our dinner plates, and has been associated with neurological and cardiovascular damage.

It is generally assumed that mercury pollution began with the Industrial Revolution; in fact, humans have been releasing mercury into the environment for thousands of years. Past research has found it stored in peat in Europe and in layers of sediment at the bottoms of lakes in South America. The ancient Greeks and Chinese used mercury as a pigment; pots of quicksilver have been found in tombs dating to about 2000 BC; and the Assyrians are thought to have used both quicksilver and cinnabar (the bright red ore in which mercury naturally occurs) as early as 1900 BC. In 1570 AD, Spanish colonists in Central and South America were using it to extract silver; 300 years later, mercury again featured in the California gold rush.

The environment does naturally