HurricanesNew levee system offers New Orleans better protection

With the busiest period of the 2013 hurricane season approaching metro New Orleans, the area is ready to face the challenge with a flood control system worth about $14.5 billion. The network of levees, floodwalls, and pumps, its designers say, should nearly eliminate the risk of flooding from most hurricanes, and substantially reduces flooding from hurricanes the size of 2005 Hurricane Katrina.

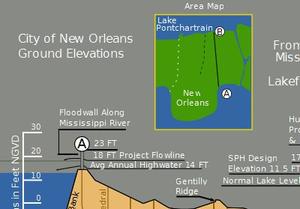

Graphic showing the depth of parts of New Orleans // Source: commons.wikimedia.org

With the busiest period of the 2013 hurricane season approaching metro New Orleans, the area is ready to face the challenge with a flood control system worth about $14.5 billion. The network of levees, floodwalls, and pumps, its designers say, should nearly eliminate the risk of flooding from most hurricanes, and substantially reduces flooding from hurricanes the size of 2005 Hurricane Katrina. The Times-Picayune reports, however, that the flood control system has limitations which encouraged Army Corps engineers and emergency preparedness officials to renew their warnings that the improvements made are aimed at protecting property, not people. Even with a flood control system put in place, damage from winds could cut off electricity for days. “Make sure you listen to local officials,” said Pat Santos, deputy director of the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness. “If they issue an evacuation recommendation, please heed that advice and leave. Don’t be a statistic; be a survivor.”

The new levee system was designed using computer modeling, engineering, and construction materials which are far more advanced than the previous levee system that failed during Hurricane Katrina. Engineers claim that property inside the levees would see minor flooding, or remain dry, even if half the interior pumping stations failed. A worst case scenario with failing pumping stations would result in floodwaters within the levee system reaching less than two feet deep. By contrast, parts of New Orleans were submerged under eight feet of water or more after Hurricane Katrina.

Understanding how levees are constructed provides insight on how engineers designed levees before and after Hurricane Katrina. Designing levees begins with the assumptions about the level of threats from hurricanes the levees are to withstand. Prior to Katrina, a “standard project hurricane,” which engineers assumed was most likely to occur, was the template used. Such a hurricane has a specific set of features: low pressure in its core, the storm’s forward speed, and how far minimum winds extended from the storm’s center. Using numbers attributed to those characteristics, engineers design the previous flood control system. These numbers, however, were based on storms that preceded Katrina, storms like the Category 3 Hurricane Betsy which caused major flooding in New Orleans in 1965.

After Katrina, the engineering community abandoned the standard project hurricane concept as outdated. The new flood control system takes into account southeastern Louisiana’s sinking soils and projected sea level rise caused by global warming. Bob Jacobsen, a Baton Rouge engineer who led a study of the near-complete East Bank levee system for the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, suggests more research about weaker, but wider and slow-moving storms. Such storms create surges of unexpected size and in unexpected areas.

The new flood control system has some challenges, but it is far better capable of preventing future flooding of the area, and more importantly, engineers and officials are consistently seeking ways to pinpoint and improve weaknesses in the current system.