GeoengineeringPromoting nuclear power to avoid geoengineering

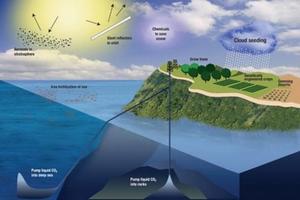

There are two basic geoengineering strategies to reduce climate change: injecting aerosols such as sulfates into the stratosphere to block a portion of the sun’s radiation and thereby cool the Earth, much as volcanic emissions do; and the large-scale removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The aerosol-injection approach is much more likely to be pursued at current stages of technological development. Scientists say that in order to avoid the need for geoengineering, which could have enormous unforeseen consequences, the international community should pursue increased deployment of nuclear power plants, which do not emit carbon dioxide, to address the climate crisis. Many climate scientists are generally supportive of nuclear engineering and less fearful of it than they are of geoengineering.

More nuclear may stop the need for geoengineering // Source: unu.edu

“I think one can argue that if we were to follow a strong nuclear energy pathway — as well as doing everything else that we can — then we can solve the climate problem without doing geoengineering.” So says Tom Wigley, one of the world’s foremost climate researchers, in the current issue of Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Refusing to take significant action on climate change now makes it more likely that geoengineering will eventually be needed to address the problem, Wigley explains in an exclusive Bulletin interview.

A SAGE release reports that in the interview, Wigley, a scientist at the University of Adelaide, Australia and at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado, explains the two basic geoengineering strategies to reduce climate change: injecting aerosols such as sulfates into the stratosphere to block a portion of the sun’s radiation and thereby cool the Earth, much as volcanic emissions do; and the large-scale removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The aerosol-injection approach is much more likely to be pursued at current stages of technological development.

To avoid the need for geoengineering, which could have enormous unforeseen consequences, the international community should pursue increased deployment of nuclear power plants, which do not emit carbon dioxide, to address the climate crisis, Wigley says. He contends that many of his colleagues in climate science are generally supportive of nuclear engineering and less fearful of it than they are of geoengineering. His pro-nuclear stance has already sparked a public backlash from climate scientists who oppose nuclear power, geoengineering, or both those methods of dealing with climate change.

“When I talk to people from any walk of life, I do talk about geoengineering,” Wigley says. “But I mostly push nuclear. Because I think one can argue that if we were to follow a strong nuclear energy pathway —as well as doing everything else that we can — then we can solve the climate problem without doing geoengineering.”

The American Association for the Advancement of Science, which named Wigley a fellow in 2003, cited “his major contributions to climate and carbon-cycle modeling and to climate data analysis.” Together with British climate researcher Sarah Raper, he introduced the widely used climate model MAGICC (Model for the Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Induced Climate Change) more than two decades ago and continues to contribute to its development.

— Read more in Dawn Stover, “Why nuclear power may be the only way to avoid geoengineering,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (13 April 2014)