Public healthManmade mercury emissions decline 30 percent between 1990 and 2010

Mercury is a metallic element that poses environmental health risks to both wildlife and humans when converted to methylmercury in ecosystems. It can be converted into gaseous emissions during various industrial activities, as well as natural processes like volcanic eruptions. Between 1990 and 2010, global mercury emissions from manmade sources declined 30 percent. New research finds.

The developed world led the way in reducing mercury emissions // Source: cuny.edu

Between 1990 and 2010, global mercury emissions from manmade sources declined 30 percent, according to a new analysis by Harvard University, Peking University, the U.S. Geological Survey, the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, and the University of Alberta. These results challenge long-standing assumptions about mercury emission trends.

Mercury is a metallic element that poses environmental health risks to both wildlife and humans when converted to methylmercury in ecosystems. It can be converted into gaseous emissions during various industrial activities, as well as natural processes like volcanic eruptions.

“For years, mercury researchers have been unable to explain the apparent conundrum between declining air concentrations and rising emission estimates,” said lead author Yanxu Zhang from Harvard University. “Our work is the first detailed, mechanistic analysis to explain the declining atmospheric mercury trend.”

USGS reports that the observed reduction in atmospheric mercury was most pronounced over North America and Europe, where several factors have contributed to the observed declines in atmospheric mercury concentrations:

- Mercury has been gradually phased out of many commercial products.

- Controls were put in place on coal-fired power plants that removed naturally occurring mercury from the coal being burned.

- Many power plants have switched to natural gas and stopped burning coal entirely, further reducing mercury emissions.

Finally, at the same time, efforts to combat acid rain resulted in controls being put in place on power plants to reduce nitrous oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions. This had the unintended benefit of also reducing mercury emissions.

“Previously, most mercury researchers subscribed to the notion that the ‘global mercury’ problem was largely manifested by a shared global emission inventory,” said USGS scientist David Krabbenhoft, one of the study’s co-authors. “However, our research shows that local and regional efforts to reduce mercury emissions matter significantly. This is great news for focused efforts on reducing exposure of fish, wildlife and humans to toxic mercury.”

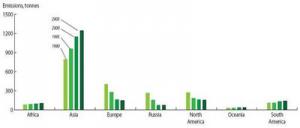

The larger-than-anticipated role of local and regional efforts on global mercury emissions explains how increases in emissions in one area can be offset by decreases in other areas. Thus, while Asian mercury emissions increased between 1990 and 2010, European and North American emission reductions during the same time were enough to more than offset the Asian increases.

“This is important for policy and decision-makers, as well as natural resource managers, because, as our results show, their actions can have tangible effects on mercury emissions, even at the local level,” said study co-author Vincent St. Louis with the University of Alberta.

The study is entitled “Observed decrease in atmospheric mercury explained by global decline in anthropogenic emissions,” and is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

— Read more in Yanxu Zhang et al., “Observed decrease in atmospheric mercury explained by global decline in anthropogenic emissions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (4 January 2016) (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516312113)