Coastal resilienceNew tool for coastal planners preparing for sea level rise

Scientists have developed a new model to help coastal planners assess the risks of sea level rise. Put to use on a global scale, it estimates that the oceans will rise at least twenty-eight centimeters on average by the end of this century — and as much as 131 cm if greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow unchecked.

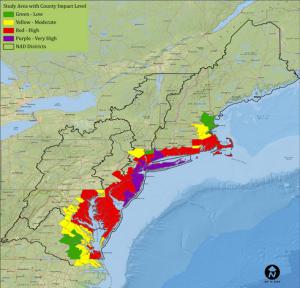

Model discloses expected result of a sea-level rise // Source: army.mil

Scientists have developed a new model to help coastal planners assess the risks of sea level rise. Put to use on a global scale, it estimates that the oceans will rise at least twenty-eight centimeters on average by the end of this century — and as much as 131 cm if greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow unchecked.

“With all the greenhouse gases we already emitted, we cannot stop the seas from rising altogether, but we can substantially limit the rate of the rise by ending the use of fossil fuels,” said co-author Anders Levermann of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the Potsdam-Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany.

Colombia U reports that the new model reconciles two common ways of estimating sea level rise, incorporating key elements of process-based methods and semi-empirical methods to create a robust, fast and accessible model.

Process-based methods capture the full physics of the processes that drive sea level rise — thermal expansion and glacier and ice sheet loss – but they are data-intensive, slow, and require powerful computers. Semi-empirical methods use the statistical relations between global mean temperature or radiative forcing and past sea level rise, making them faster and more accessible, but they often lack the detail that incorporating the physics can provide. The new contribution-based semi-empirical approach starts with a semi-empirical method and incorporates information on each contributor to sea level rise, including long-term commitment, possible saturation and response timescale. The scientists are making the computer code available for coastal planners and other experts to use in risk assessments.

“We try to give coastal planners what they need for adaptation planning, be it building dikes, designing insurance schemes for flooding, or mapping long-term settlement retreat,” Levermann said.

Levermann and his colleagues describe the new model and its results in estimating global sea level rise in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The results are consistent with both past observations and long-term sensitivities found in process-based simulations, the authors write.

This is what the model shows for three of the emissions scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

- If the world significantly scales back its use of fossil fuels and cuts emissions quickly — a trajectory more ambitious than anything governments have agreed to internationally — sea level would rise 28-56 cm over the 1986-2005 average by the year 2100, based on calculations using the IPCC’s RCP2.6 emissions pathway.

- If governments meet their emissions-reduction commitments (in the range of RCP4.5), sea level would rise 37-77 cm by 2100. The greatest contributor over the current century would be thermal expansion of the warming oceans, at 9-30 cm, but changes in the ice sheets would be underway.

- If emissions grow substantially (RCP8.5), sea level would rise between 57 cm and 131 cm by the year 2100.

Looking to the end of this century is useful for immediate coastal planning, but it only provides a glimpse into the impact that greenhouse gas emissions from human activities today will have on the planet far into the future. The polar ice sheets are slow to respond, and their ice loss — Antarctica and Greenland together hold enough ice to raise sea level about 65 meters — will continue long after emissions are brought down.

Columbia U notes that in a study published earlier this month, Levermann and colleagues looked at the impact emissions now and in the near future will have for future generations over the next 10,000 years. Their findings reflect the value of immediate, ambitious action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and of long-term planning: under a scenario in which temperatures rise even 2°C, several of the world’s coastal megacities would eventually be submerged without extraordinary protective efforts.

— Read more in Matthias Mengel et al., “Future sea level rise constrained by observations and long-term commitment,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (22 February 2016) (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500515113)