Public healthResearchers develop next generation antibiotics to combat drug-resistant "superbugs"

Each year 90,000 people in the United States die of drug-resistant “superbugs” — bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a deadly form of staph infection resistant to normal antibiotics; certain bacterial strains include enzymes which help the bacteria to inactivate antibiotics — and a team of researchers are working on turning this powerful mechanism against the bacteria itself

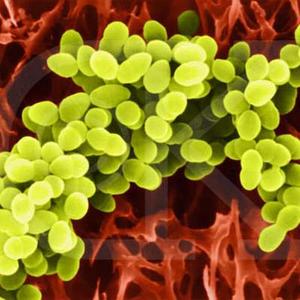

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) // Source: chrisdellavedova.com

Antibiotics can work miracles, knocking out common infections like bronchitis and tonsillitis. According to the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), however, each year 90,000 people in the United States die of drug-resistant “superbugs” — bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a deadly form of staph infection resistant to normal antibiotics. Although hospital patients are particularly susceptible as a result of open wounds and weakened immune systems, the bacteria can infect anyone.

Dr. Micha Fridman of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Chemistry is now developing the next generation of antibiotics designed to overcome this kind of bacteria. The key, he says, is in the bacteria itself.

“We took the mechanism of bacterial resistance and used this mechanism itself to generate antibiotics,” explains Fridman. “It’s thanks to these bacteria that we can develop a better medication.” Conducted in collaboration with Professor Sylvie Garneau-Tsodikova from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, Fridman’s research was highlighted recently in the journal ChemBioChem.

Fighting from within

According to Fridman, certain bacterial strains include enzymes which help the bacteria to inactivate antibiotics. When the enzymes meet with these antibiotics, they chemically alter the drug, making the antibiotic ineffective and unable to recognize its target.

Turning this powerful mechanism against the bacteria itself, the team isolated the antibiotic-inactivating enzymes from the bacteria, then integrated them into the drugs. With this alteration, the modified antibiotics proved to be effective against typically resistant bacterial strains.

At the heart of this development, says Fridman, was the chemical modification of the parent drug. Once the researchers identified how the bacteria incapacitated the antibiotics, they were able to create a drug that could block bacterial resistance while maintaining the integrity of the antibiotic.

Killing bacteria, saving lives

These new antibiotics will be a vast improvement on today’s drugs, says Fridman. When fully developed, they could be used to treat infections that are now considered difficult if not impossible to treat with current antibiotics.

Fridman says that, while the new antibiotics are a few years away from the marketplace, the ability to beat bacterial resistance will be invaluable for the future of health care.