-

World can be separated into seven regions for vectored human diseases

Researchers have for the first time mapped human disease-causing pathogens, dividing the world into a number of regions where similar diseases occur. The findings show that the world can be separated into seven regions for vectored human diseases — diseases which are spread by pests, like mosquito-borne malaria — and five regions for non-vectored diseases, like cholera.

-

-

World's response to Ebola slow, inconsistent, inadequate: Médecins sans Frontières

The NGO Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) has harshly criticized the international community for its slow and inconsistent response to the Ebola crisis in West Africa. MSF says the world’s response risks creating “a double failure” because ill-equipped locals in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea have been left to run hospitals and treatment centers. MSF international president, Dr. Joanne Liu, said it was “extremely disappointing that states with biological-disaster response capacities have chosen not to deploy them.”

-

-

Satellites help assess risk of epidemics

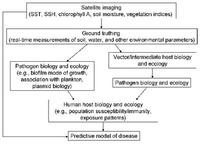

Changes in the environment, global trade, and travel are all factors in the ever-increasing numbers and movement of pests. Identifying and predicting the distribution of existing local species as well as the spread of new exotic ones are essential in assessing the risk of potential epidemics. Researchers have developed Vecmap — an all-encompassing software and services package including a smartphone app for field studies with a time and location information system, all linked to an online database. The database pools satellite information with results from field research, and satnav adds location information. The new approach greatly reduces the complexity of tracking species compared to traditional methods.

-

-

Portable, fast Ebola test kit in trials in Guinea

Scientists say that early diagnosis is key to surviving Ebola once a person has been infected. Roughly 50 percent of those known to be infected with Ebola have died, but scientists hope to reduce the number as a new test designed to diagnose the Ebola virus in humans in under fifteen minutes will be tried out at a treatment center in Conakry, Guinea. The test is six times faster than tests currently used in West Africa.The mobile testing device is one of six projects jointly funded by Wellcome and the U.K.’s Department for International Development under the 6.5 million pounds Research for Health in Humanitarian Crises initiative.

-

-

NIAID/GSK experimental Ebola vaccine appears safe, prompts immune response

An experimental vaccine to prevent Ebola virus disease was well-tolerated and produced immune system responses in all twenty healthy adults who received it in a phase 1 clinical trial conducted by researchers from the National Institutes of Health. The results from the NIH Phase 1 clinical trial will support accelerated development of candidate vaccine.

-

-

Developing a global workforce to tackle emerging pandemic threats

When a new pandemic threat like this year’s Ebola outbreak emerges, the importance of preventing and limiting disease spread becomes apparent. Well-trained global health professionals play a key role in preventing and responding to emerging zoonotic disease. Under a new 5-year award of up to $50 million, the University of Minnesota and Tufts University will be part of an international partnership of universities to strengthen global workforce development against emerging pandemic threats.

-

-

Public health officials work to ensure that the lessons of Ebola are not forgotten

Hospitals find it difficult to remain fully prepared for disease outbreaks because they rarely occur and preparation and frequent training are expensive. Public health professionals and infectious disease experts are working to ensure that lessons learned and protocols put in place in response to the Ebola outbreak will be used to prevent and respond to future virus and disease outbreaks.

-

-

Pre-empting flu evolution may make for better vaccines

Influenza is a notoriously difficult virus against which to vaccinate. There are many different strains circulating — both in human and animal populations — and these strains themselves evolve rapidly. Yet manufacturers, who need to produce around 350 million doses ahead of the annual flu season, must know which strain to put in the vaccine months in advance — during which time the circulating viruses can evolve again. An international team of researchers has shown that it may be possible to improve the effectiveness of the seasonal flu vaccine by “pre-empting” the evolution of the influenza virus.

-

-

U.S. will not see an Ebola epidemic – not even a serious outbreak: Scientists

Twenty-five years ago, the United States experienced its first Ebola outbreak in a Reston, Virginia primate facility which shipped animals to research labs throughout the country. Jerry Jaax, one of the scientists who worked at the primate facility at the time and who is now an associate vice president for research compliance and university veterinarian at Kansas State University, believes that the United States is well prepared to handle the Ebola virus. “We won’t have an epidemic or even a serious outbreak,” said Jerry Jaax. “The thing about it is we’ve got a zero risk tolerance bar that we set that says we can’t afford to have one person get infected or it’s a disaster. You can’t ever say never in biology and there are a lot of wild cards thrown in there, but I think basically the United States is ready.”

-

-

Ebola discussion in U.S. driven by fear, not science: Infectious disease experts

A significant part of the Ebola debate in the United States has been driven by fear, not science, according to infectious disease experts. Despite assurances from public health officials, the general public continues to be fearful of an Ebola outbreak in the United States. Some states have imposed mandatory quarantines for all healthcare workers returning from Ebola-stricken West Africa, even if they show no symptoms.”The fear is trumping science,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association.

-

-

Searching for weapons in the fight against drug-resistant bacteria

Researchers are taking a very close look at bacterial cells in hopes of figuring out how to stop the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria known as CRE, or carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Dubbed the “nightmare bacteria,” CRE infections are immune to even the strongest antibiotics and have the ability to transfer that drug resistance to other bacteria. The infections, which can lead to pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, and more, have a 50 percent mortality rate. “That’s worse than Ebola,” says one researcher.

-

-

Epidemics do not require long-distance travel by virus carriers to spread

The current Ebola outbreak shows how quickly diseases can spread with global jet travel. Yet knowing how to predict the spread of these epidemics is still uncertain, because the complicated models used are not fully understood. Using a very simple model of disease spread, UC Berkeley biophysicist Oskar Hallatschek proved that one common assumption is actually wrong. Most models have taken for granted that if disease vectors, such as humans, have any chance of “jumping” outside the initial outbreak area — by plane or train, for example – the outbreak quickly metastasizes into an epidemic. Hallatschek and colleagues found instead that if the chance of long-distance dispersal is low enough, the disease spreads quite slowly, like a wave rippling out from the initial outbreak. This type of spread was common centuries ago when humans rarely traveled. The Black Death spread through fourteenth-century Europe as a wave, for example.

-

-

U.S. will see between 1 and 130 additional Ebola cases by end of 2014: Experts

Top U.S. medical experts studying the spread of Ebola predict a few more cases will reach America before year’s end, citing the return of healthcare workers currently working in West Africa as the most likely cause of new cases. Using data models that weigh several variables including daily new infections in West Africa, global airline traffic, and transmission possibilities, top infectious disease experts predict as few as one or two additional infections and as many as 130 by the end of 2014.

-

-

Hungarian red mud spill did little long-term damage

The aftereffects of the 2010 red mud spill that threatened to poison great swathes of the Hungarian countryside have turned out to be far less harmful than scientists originally feared. The disaster happened when weeks of heavy rain caused a dam to collapse at a containment facility in Ajka in Western Hungary. It released around a million cubic meters of toxic sludge into the Torna-Marcal river system, onto the Hungarian plain and ultimately into the Danube. The mud, a byproduct of refining aluminum from bauxite ore, was dangerously alkaline, extremely salty and contained potentially toxic metals like chromium and vanadium.

-

-

Rate of infection in West Africa has begun to slow down

Public health officials monitoring the Ebola epidemic in West Africa say the outbreak may have reached a turning point in which transmissions may have begun to slow down. Dr. Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, the organization funding a series of fast-tracked trials of Ebola vaccines and drugs, says that although the virus will continue to infect people in the months ahead, “it is finally becoming possible to see some light.”

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies