-

U.S. response to Zika: Fragmented and uneven

How is the United States responding to Zika? CDC is doing what it can to support efforts to halt disease transmission and support state and local government. But on 30 August CDC director Tom Frieden announced that the agency had almost run out of money to fight the virus. Congress has yet to pass a funding bill, leaving the Obama administration to redirect money earmarked for other purposes to support Zika research and response efforts. The response so far seems fragmented, and even somewhat contentious – not unlike the response to the Ebola crisis in the United States in 2014. The response to that public health crisis was shaped by the fragmented and partisan U.S. political system, not by epidemiology or medicine.

-

-

Data sharing should become routine for best response to public health emergencies

The recent outbreaks caused by Ebola and Zika viruses have highlighted the importance of medical and public health research in accelerating outbreak control and have prompted calls for researchers to share data rapidly and widely during public health emergencies. However, the routine practice of data sharing in scientific research, rather than reactive data sharing, will be needed to effectively prepare for future public health emergencies.

-

-

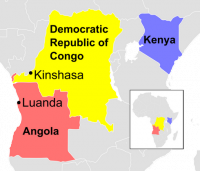

Yellow Fever outbreak on verge of going global, with vaccine supply running short

The largest Yellow Fever epidemic for decades is now sweeping the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola and could soon spread to the Americas, Asia, and Europe. The outbreak has all but emptied global emergency stocks of vaccine. There are only seven million emergency vaccines available for the current vaccination campaign — too few to even fully cover the city of Kinshasa, let alone the whole of the DRC.

-

-

$2.3 million grant for Ebola vaccine research

The Center of Excellence for Emerging Zoonotic and Animal Diseases, or CEEZAD, at Kansas State University will use a $2.3 million federal grant to study the safety in livestock of a newly developed vaccine to protect humans from the Ebola Zaire virus. No infectious Ebola virus will be used in the Biosecurity Research Institute during the studies.

-

-

Three ways synthetic biology could annihilate Zika and other mosquito-borne diseases

There are tried and tested approaches in the arsenal of weapons against the mosquito-borne disease, but to combat Zika and other mosquito-borne disease, more is needed. Gene drives, synthetic biology-based genetic engineering techniques, offer one solution by reengineering mosquitoes or obliterating them altogether. Yet we still have only the vaguest ideas of how the systems we’re hacking by using gene drives actually work. It’s as if we’ve been given free rein to play with life’s operating system code, but unlike computers, we don’t have the luxury of rebooting when things go wrong. As enthusiasm grows over the use of synthetic biology to combat diseases like Zika, greater efforts are needed to understand what could go wrong, who and what might potentially be affected, and how errors will be corrected.

-

-

Influenza outbreak would cost U.S. billions of dollars in losses

An influenza pandemic would cost the nation tens of billions of dollars in economic losses — nearly double what previous estimates showed, a new study reveals. The study, which was funded by the National Biosurveillance Integration Center of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, found that the nation would lose as much as $45 billion in gross domestic product if Americans failed to get vaccinated for the flu, compared with $34 billion if they were vaccinated.

-

-

The politicization of U.S. handling Ebola may carry over to Zika

If the United States responds to Zika the way it did to Ebola — and early indications are that in many ways it is — the country can expect missteps brought about by a lack of health care coordination and a lot of political finger pointing, according to a new analysis. The researchers studied the U.S. response to Ebola and found a fragmented system with no clear leadership, and considerable “strategic politicization” due to the outbreak’s arrival during a midterm election year.

-

-

U.S. needs greater preparation for next severe public health threats: Experts panel

In a report released last week by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), an Independent Panel formed to review HHS’s response to Ebola made several recommendations on how the nation’s federal public health system should strengthen its response to major public health threats, both internationally and domestically. “Without focused and sustained effort, the result of other novel public health threats could be much more devastating,” said the chairman of the Independent Panel.

-

-

Lessons of 1976 Ebola outbreak analysis are relevant today

With the recent Ebola epidemic in West Africa reviving interest in the first outbreak of the deadly hemorrhagic fever 40 years ago, scientists have released a report highlighting lessons learned from the smaller, more quickly contained 1976 outbreak. “Key to diagnosis in 1976 was the relatively quick clinical recognition of a severe, possibly new disease by national authorities,” according to one of the researchers.

-

-

Bolstering international response capabilities to infectious disease threats

To make the world safer against future infectious disease threats, national health systems should be strengthened, the World Health Organization’s emergency and outbreak response activities should be consolidated and bolstered, and research and development should be enhanced, experts say

-

-

How will the next leader of WHO tackle future health emergencies?

In light of heavy criticism of the World Health Organization’s handling of the Ebola outbreak, the election process for the next director general will be under intense scrutiny. Experts outline the key questions on epidemic preparedness for prospective candidates.

-

-

Yellow fever epidemic threatens new global health emergency

Evidence is mounting that the current outbreak of yellow fever is becoming the latest global health emergency, two experts say, calling on the World Health Organization (WHO) to convene an emergency committee under the International Health Regulations. In addition, with frequent emerging epidemics, they call for the creation of a “standing emergency committee” to be prepared for future health emergencies. The add that vaccine “supply shortages could spark a health security crisis.”

-

-

Cellphone-sized device detects the Ebola virus quickly

The worst of the recent Ebola epidemic is over, but the threat of future outbreaks lingers. Monitoring the virus requires laboratories with trained personnel, which limits how rapidly tests can be done. Now scientists report in ACS’ journal Analytical Chemistry a handheld instrument that detects Ebola quickly and could be used in remote locations.

-

-

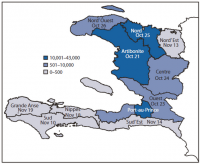

Haiti’s cholera epidemic could have been prevented with low-cost approaches

Haiti’s cholera epidemic killed close to 9,000 people and hospitalized hundreds of thousands more. The epidemic also spread to several neighboring countries. Cholera remains a critical risk for UN peacekeeping operations, years after Nepalese troops inadvertently introduced the disease to Haiti in fall of 2010 and triggered one of the worst epidemics in recent years. Researchers have found that simple and inexpensive interventions — which the United Nations has yet to implement — would be effective in preventing future outbreaks of the bacterial infection.

-

-

Efficient alternative for Ebola screening program for travelers

As of 31 January 2016, a total of 28,639 cases and 11,316 deaths have been attributed to Ebola, figures that are assumed to significantly underestimate the actual scope of the 2014 Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever outbreak in West Africa. In the United States, there were also two imported cases and two locally acquired cases reported in September-October 2014. Researchers offer an alternative policy for Ebola entry screening at airports in the United States. “Security measures implemented after 9/11 taught us a lot about what not to do,” one of the researchers say. “We learned that finding the one person who intends to do harm out of several million passengers is akin to finding a needle in a haystack.”

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies