-

New plant growth technology may alleviate climate change, food shortage

A research team has developed a new strategy to promote plant growth and seed yield by 38 percent to 57 percent in a model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, hence increasing CO2 absorption from the atmosphere. This technology may also have potential in boosting food production and thus could solve another danger of human civilization: food shortage due to overpopulation.

-

-

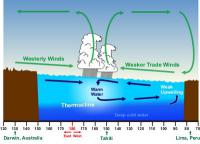

Coming El Nino could replenish Calif.’s aquifers – or ravage vulnerable infrastructure

When respected climatologists describe this winter’s warming of tropical Pacific waters as a Godzilla El Nino event, they might be onto something. The science fiction monster’s signature move is to emerge from the ocean and destroy structures built by hapless humans. Many of the necessary plot elements are in place for El Nino to similarly wreak havoc in the Golden State in the coming months, says an expert.

-

-

Humanity has become a geological force: Scientists

Humanity has become a geological force which is able to suppress the beginning of the next ice age, a study now published in the renowned scientific journal Nature shows. “Like no other force on the planet, ice ages have shaped the global environment and thereby determined the development of human civilization. For instance, we owe our fertile soil to the last ice age that also carved out today’s landscapes, leaving glaciers and rivers behind, forming fjords, moraines and lakes. However, today it is humankind with its emissions from burning fossil fuels that determines the future development of the planet,” says one expert.

-

-

Nepal’s destructive post-earthquake landslides raise parallels for Pacific Northwest

Following the Nepal earthquake — even during the dry season when soils were the most stable — there were tens of thousands of landslides in the region. These landslides caused pervasive damage as they buried towns and people, blocked rivers, and closed roads. Expert estimate that the Nepal earthquake might have caused between 25,000 and 60,000 landslides. The subduction zone earthquake likely to occur in the future of the Pacific Northwest is expected to be larger than the event in Nepal.

-

-

The impact of rising sea levels on Rhode Island

Climate change will bring profound changes to Rhode Island’s coastal communities in the coming decades. Scientists project sea levels to rise 3 to 5 feet in the state by 2100, and recent government projections are as high as 7 feet. Now, University of Rhode Island students are studying one community that could be hit especially hard: Matunuck. The year-long analysis by eight senior ocean engineering students is so thorough that flooding projections were made for specific structures —709 to be exact. Those home and business owners will be able to find out what could happen to their buildings during a powerful storm with rising sea levels up to five feet.

-

-

Dawn of the Anthropocene: five ways we know humans have triggered a new geological epoch

Is the Anthropocene real? That is, the vigorously debated concept of a new geological epoch driven by humans. Our environmental impact is indeed profound — there is little debate about that — but is it significant on a geological timescale, measured over millions of years? And will humans leave a distinctive mark upon the layers of rocks that geologists of 100,000,000AD might use to investigate the present day? The human-driven changes to the Earth’s environment are comparable in scale to those of earlier epochs. The extraordinarily wide range of geological signals associated with the Anthropocene means comparison with earlier epochs is not straightforward, but the evidence indicates an overall magnitude of change at least as large as that which ushered in the Holocene, our current geological epoch, and most other epochs. It means that humans are moving the Earth system from the comparative environmental stability of the Holocene into a new, evolving planetary state. And the impact will be felt by all human generations to come.

-

-

Record December boosted 2015 to second warmest year for contiguous U.S.

The 2015 annual average U.S. temperature was 54.4°F, 2.4°F above the twentieth century average, the second warmest year on record. Only 2012 was warmer for the United States with an average temperature of 55.3°F. This is the nineteenth consecutive year the annual average temperature exceeded the twentieth century average. The first part of the year was marked by extreme warmth in the West and cold in the East, but by the end of 2015, record warmth spanned the East with near-average temperatures across the West. This temperature pattern resulted in every state having an above-average annual temperature.

-

-

The Anthropocene: Hard evidence for a new, human-driven geological epoch

The evidence for a new geological epoch which marks the impact of human activity on the Earth is now overwhelming, according to a recent paper by an international group of geoscientists. The Anthropocene, which is argued to start in the mid-twentieth century, is marked by the spread of materials such as aluminum, concrete, plastic, fly ash, and fallout from nuclear testing across the planet, coincident with elevated greenhouse gas emissions and unprecedented trans-global species invasions. The researchers set out to anser this question: To what extent are human actions recorded as measurable signals in geological strata, and is the Anthropocene world markedly different from the stable Holocene Epoch of the last 11,700 years which allowed human civilization to develop?

-

-

Redirected flood waters leading to unintended consequences

An intricate system of basins, channels, and levees called the Headwaters Diversion carries water from the eastern Missouri Ozark Plateau to the Mississippi River south of Cape Girardeau. The system protects 1.2 million acres of agricultural lands from both overflow from the Mississippi River during flooding events and from Ozark Plateau runoff. Climate scientists predict a continued pattern of extreme rainfall events in the upper Mississippi River region, suggesting that unexpected above average rainfall events in the Ohio and Mississippi River basins will continue to increase the frequency of extreme flooding events on these rivers.

-

-

Drought, heat deleterious for global crops

Drought and extreme heat slashed global cereal harvests between 1964 and 2007 — and the impact of these weather disasters was greatest in North America, Europe, and Australasia. At a time when global warming is projected to produce more extreme weather, a new study provides the most comprehensive look yet at the influence of such events on crop area, yields, and production around the world.

-

-

Current pace of environmental change unprecedented in Earth’s history

Researchers have further documented the unprecedented rate of environmental change occurring today, compared to that which occurred during natural events in Earth’s history. The environmental change in the past “appears to have been far slower than that of today, taking place over hundreds of thousands of years, rather than the centuries over which human activity is increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels,” says a leading expert.

-

-

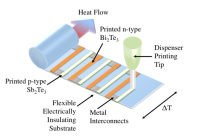

Extreme weather increasingly threatening U.S. power grid

Power outages related to weather take out between $18 billion to $33 billion from the nation’s economy. Analysis of industry data found that these storms are a growing threat to, and the leading cause of outages in, the U.S. electric grid. The past decade saw power outages related to bad weather increase, which means that power companies must find a way address this problem.

-

-

Global electricity production vulnerable to climate change, water resource decline

Climate change impacts and associated changes in water resources could lead to reductions in electricity production capacity for more than 60 percent of the power plants worldwide from 2040-2069. A new study calls for a greater focus on adaptation efforts in order to maintain future energy security. Making power plants more efficient and flexible could mitigate much of the decline.

-

-

Large and growing methane emissions from northern lakes

Methane is increasing in the atmosphere, but many of its sources are poorly understood. Climate-sensitive regions in the north are home to most of the world’s lakes. New research shows that these northern freshwaters are critical emitters of methane, a more effective greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

-

-

Refugees in Germany; Swedish border checks; ISIS’s British medics; U.K. flood defenses

German economist says Germany should expect a tough competition between refugees and poorer Germans; Sweden, as of midnight Sunday, began to impose strict identity checks of all travelers from Denmark; a British delegation, including an imam from London, has traveled to Sudan to try to dissuade young British doctors from joining ISIS; as parts of the United Kingdom braced themselves for more misery, the government’s storm-related actions are criticized.

-

More headlines

The long view

The Surprising Reasons Floods and Other Disasters Are Deadlier at Night

By Kate Yoder

It’s not just that it’s dark and people are asleep. Urban sprawl, confirmation bias, and other factors can play a role.

Why Flash Flood Warnings Will Continue to Go Unheeded

By Rebecca Egan McCarthy

Experts say local education and community support are key to conveying risk.