Self-healing concrete developed

University of Rhode Island researchers develop a new type of self-healing concrete that promises to be commercially viable and have added environmental benefits; a microencapsulated sodium-silicate healing agent is embedded directly into a concrete matrix; when tiny stress cracks begin to form in the concrete, the capsules rupture and release the healing agent into the adjacent areas

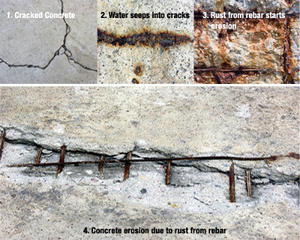

Various forms of concrete deterioration // Source: primerestorationinc.com

A graduate student at the University of Rhode Island has developed a new type of self-healing concrete that promises to be commercially viable and have added environmental benefits.

To create the self-healing material, Michelle Pelletier embedded a microencapsulated sodium-silicate healing agent directly into a concrete matrix. When tiny stress cracks begin to form in the concrete, the capsules rupture and release the healing agent into the adjacent areas (compare this method to the one developed by researchers at the University of Michigan: “Self-healing concrete for safer, durable, and cheaper-to-maintain infrastructure,” 23 April 2009 HSNW).

The sodium silicate reacts with the calcium hydroxide naturally present in the concrete to form a calcium-silica-hydrate product that heals the cracks and blocks the pores in the concrete. The chemical reaction creates a gel-like material that hardens in about one week.

“Smart materials usually have an environmental trigger that causes the healing to occur,” explained Pelletier, who is collaborating on the project with URI Chemical Engineering professor Arijit Bose. “What’s special about our material is that it can have a localized and targeted release of the healing agent only in the areas that really need it.”

In tests comparing a standard concrete mix to concrete containing two per cent sodium-silicate healing agent, Pelletier’s healing mix recovered 26 percent of its original strength (after being stressed to near breaking) versus 10 per cent recovery by the standard mix. Pelletier said that an increase in the quantity of healing agent would likely further improve the recovered strength of the concrete.

So far, efforts to extend the life of structures and reduce repair costs have led engineers to develop smart materials that have self-healing properties, but many of these new materials are difficult to commercialize.

Pelletier noted that some researchers have laced the concrete with bacteria spores that secrete calcium carbonate to fill the cracks and pores, while others embedded glass capillaries with a healing agent, but the process of filling the capillaries with the agent is long and tedious.

Corrosion inhibitor

Next up for Pelletier is a study to see whether her sodium-silicate healing agent could also act as a corrosion inhibitor. “Building concrete is routinely fixed with steel reinforcement bars to compensate for low tensile strength, but they are extremely susceptible to corrosion,” Pelletier said. “We are exploring to see if the release of the agent will result in corrosion inhibition by two mechanisms. First, the reduced water transport due to the filled pores and reduced interconnectivity within the matrix may result in less moisture reaching the metal, and ultimately less corrosion. Also, silicates can deposit on the surface to form a protective film, which may also help with reducing the corrosion rate of the steel rebars.”

Environmental advantages

One additional advantage to the use of self-healing concrete is that it could reduce the significant CO2 emissions that result from concrete production.

Because the production of concrete is very energy intensive — when mining, transportation, and concrete plants are considered — the industry is responsible for about 10 percent of all CO2 emissions in the US.

“If self-healing concrete can lengthen the life of the concrete and reduce maintenance and repairs, it will ultimately reduce the production of excess amounts of concrete and result in a decrease in CO2 emissions,” she said.