-

Former IAEA deputy director criticizes nuclear agency’s Iran investigations

Olli Heinonen, the former deputy director-general of the International Atomic Energy Agency has criticized the agency for “reduc[ing] the level of transparency and details in its reporting” on Iran’s nuclear program, making it “practically impossible” to confirm that Iran is complying with the terms of the nuclear deal.

-

-

First large-scale, citywide test of advanced radioactive threat detection system

Field testing of more than 1,000 networked, mobile radiation sensors in Washington, D.C., yields valuable data for implementing enhanced radiation-detection networks in major U.S. cities. By getting volunteers to walk all day looking for clues, the DARPA-sponsored exercise provided the largest test yet of DARPA’s SIGMA program, which is developing networked sensors that can provide dynamic, real-time radiation detection over large urban areas.

-

-

Nuclear CSI: Noninvasive procedure could spot criminal nuclear activity

Determining whether an individual – a terrorist, a smuggler, a criminal — has handled nuclear materials, such as uranium or plutonium, is a challenge national defense agencies currently face. The standard protocol to detect uranium exposure is through a urine sample; however, urine is able only to identify those who have been recently exposed. Scientists have developed a noninvasive procedures that will better identify individuals exposed to uranium within one year.

-

-

HHS bolsters U.S. health preparedness for radiological threats

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) says that as a part of its mission to help protect Americans’ health following even the most unthinkable of disasters, it is purchasing two medical products to treat injuries to bone marrow in victims of radiological or nuclear incidents. Bone marrow is essential to producing blood.

-

-

Assessing the risk from Africa as Libya loses its chemical weapons

Libya’s remaining chemical weapons left over from the Gaddafi regime are now being safely disposed of in a German facility. This eliminates the risk of them falling into the wrong hands. But can these same hands acquire weapons of mass destruction from the rest of Africa? The disposal of Libya’s chemical weapons has lowered the risk of weapons of mass destruction in Africa. But we have seen how far non-state actors are willing to go to either produce or steal such weapons. For example, analysts envision militants known as “suicide infectors” visiting an area with an infectious disease outbreak like Ebola purposely to infect themselves and then using air travel to carry out the attack. Reports from 2009 show forty al-Qaeda linked militants being killed by the plague at a training camp in Algeria. There were claims that they were developing the disease as a weapon. The threat WMD pose cannot be ignored. African countries, with help from bilateral partners and the international community, have broadened their nonproliferation focus. They will need to keep doing so if the goal is effectively to counter this threat.

-

-

Iran received secret exemptions from complying with some facets of nuclear deal

The nuclear deal between the P5+1 powers and Iran – the official named is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) — placed detailed limitations on facets of Iran’s nuclear program that needed to be met by Implementation Day, which took place on 16 January 2016. Most of the conditions were met by Iran, but some nuclear stocks and facilities were not in accordance with JCPOA limits on Implementation Day. In anticipation, the Joint Commission had earlier and secretly exempted them from the JCPOA limits. “Since the JCPOA is public, any rationale for keeping these exemptions secret appears unjustified,” say two experts. “Moreover, the Joint Commission’s secretive decision making process risks advantaging Iran by allowing it to try to systematically weaken the JCPOA. It appears to be succeeding in several key areas.”

-

-

A new generation of low-cost, networked, nuclear-radiation detectors

A DARPA program aimed at preventing attacks involving radiological “dirty bombs” and other nuclear threats has successfully developed and demonstrated a network of smartphone-sized mobile devices that can detect the tiniest traces of radioactive materials. Combined with larger detectors along major roadways, bridges, other fixed infrastructure, and in vehicles, the new networked devices promise significantly enhanced awareness of radiation sources and greater advance warning of possible threats.

-

-

Looking from space for nuclear detonations

Sandia has been in the business of nuclear detonation detection for more than fifty years, starting with the 1963 launch of the first of twelve U.S. Vela satellites to detect atmospheric nuclear testing and verify compliance with the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963 and subsequently the Threshold Test Ban Treaty of 1974. That marked the start of the U.S. Nuclear Detonation Detection System that supports treaty monitoring. The Global Burst Detection (GBD) system launched 5 February from Cape Canaveral aboard the 70th Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite. The GBD looks for nuclear detonations around the world, offering real-time information about potential activity to U.S. policymakers. The launch was the 12th and final of the Block IIF (GPSIIF) series of GPS satellites in medium Earth orbit.

-

-

Melting ice sheet could release frozen cold war-era radioactive waste

Camp Century, a U.S. military base built within the Greenland Ice Sheet in 1959, was decommissioned in 1967, and its infrastructure and waste were abandoned under the assumption they would be entombed forever by perpetual snowfall. But climate change has warmed the Arctic more than any other region on Earth, and as portion of the ice sheet covering Camp Century melt, the camp’s infrastructure will become exposed, and any remaining biological, chemical, and radioactive waste could re-enter the environment.

-

-

Scanners more rapidly and accurately identify radioactive materials at U.S. borders, events

Among the responses to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, DHS, among other things, has increased screening of cargo coming into the country. At MIT, the terrorist attacks gave rise to a company dedicated to helping DHS — and, ultimately, other governments and organizations worldwide — better detect nuclear and other threats at borders and seaports. Today, Passport — co-founded in 2002 by MIT physics professor emeritus William Bertozzi — has two commercial scanners: the cargo scanner, a facility used at borders and seaports; and a wireless radiation-monitoring system used at, for example, public events.

-

-

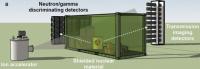

Improving detection of concealed nuclear materials

Researchers have demonstrated proof of concept for a novel low-energy nuclear reaction imaging technique designed to detect the presence of “special nuclear materials” — weapons-grade uranium and plutonium — in cargo containers arriving at U.S. ports. The method relies on a combination of neutrons and high-energy photons to detect shielded radioactive materials inside the containers.

-

-

Helping inspectors locate and identify underground nuclear tests

Through experiments and computer models of gas releases, scientists have simulated signatures of gases from underground nuclear explosions (UNEs) that may be carried by winds far from the point of detonation. The work will help international inspectors locate and identify a clandestine UNE site within a 1,000 square kilometer search area during an on-site inspection that could be carried out under the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

-

-

Nuclear forensics support law enforcement, national security investigations

According to the IAEA, in the period from 1993 to 2013, sixteen confirmed incidents involved the unauthorized possession of HEU or plutonium. Researchers have just published an overview of nuclear forensics, including examples of key nuclear forensic signatures that have allowed investigators to elucidate the history of unknown nuclear material and describing how nuclear forensics supports law enforcement and national security investigations.

-

-

Software helps detect nuclear tests

When North Korea conducted its recent nuclear weapon test, it was not terribly difficult to detect. It was a fairly large blast, it occurred in a place where a test was not surprising, and the North Korean government made no effort to hide it. But clandestine tests of smaller devices, perhaps by terrorist organizations or other nonstate actors, are a different story. It is those difficult-to-detect events that the Vertically Integrated Seismic Analysis (VISA) — a machine learning system — aims to find.

-

-

Pairing seismic data, radionuclide fluid-flow models to detect underground nuclear tests

Underground nuclear weapon testing produces radionuclide gases that may seep to the surface, which is affected by many factors. These include fractures in the rock caused by the explosion’s shock waves that create pathways for the gas to escape plus the effect of changes in atmospheric pressure that affect the gases’ movement. Scientists have developed a new, more thorough method for detecting underground nuclear explosions (UNEs) by coupling two fundamental elements — seismic models with gas-flow models — to create a more complete picture of how an explosion’s evidence (radionuclide gases) seep to the surface.

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies