Planetary securityAsteroids: Earth will be hit by a shotgun blast instead of a single cannonball

Scientists find that many asteroids are not solid rocks, but a collection of small gravel-sized rocks, held together by gravity; instead of a solid mountain colliding with Earth’s surface, the planet would be pelted with the innumerable pebbles and rocks of which it is composed, like a shotgun blast instead of a single cannonball; this knowledge could guide the defensive tactics to be taken if an asteroid were on track to collide with the Earth

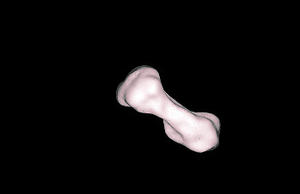

Asteroid Kleopatra // Source: meteorite-recon.com

Though it was once believed that all asteroids are giant pieces of solid rock, later hypotheses have it that some are actually a collection of small gravel-sized rocks, held together by gravity. If one of these “rubble piles” spins fast enough, it is speculated that pieces could separate from it through centrifugal force and form a second collection — in effect, a second asteroid.

Now researchers at Tel Aviv University, in collaboration with an international group of scientists, have proved the existence of these theoretical “separated asteroid” pairs.

Ph.D. student David Polishook of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences and his supervisor, Dr. Noah Brosch of the university’s School of Physics and Astronomy, say the research has not only verified a theory, but could have greater implications if an asteroid passes close to Earth. Instead of a solid mountain colliding with Earth’s surface, says Dr. Brosch, the planet would be pelted with the innumerable pebbles and rocks of which it is composed, like a shotgun blast instead of a single cannonball. This knowledge could guide the defensive tactics to be taken if an asteroid were on track to collide with the Earth.

A large part of the research for the study, recently published in the journal Nature, was done at Tel Aviv University’s Wise Observatory, located deep in the Negev Desert — the first and only modern astronomical observatory in the Middle East.

Spinning out in space

According to Brosch, separated asteroids are composed of small pebbles glued together by gravitational attraction. Their paths are affected by the gravitational pull of major planets, but the radiation of the sun, he says, can also have an immense impact. Once the sun’s light is absorbed by the asteroid, rotation speeds up. When it reaches a certain speed, a piece will break off to form a separate asteroid.

The phenomenon can be compared to a figure skater on the ice. “The faster they spin, the harder it is for them to keep their arms close to their bodies,” explains Brosch.

As a result, asteroid pairs are formed, characterized by the trajectory of their rotation around the sun. Though they may be millions of miles apart, the two asteroids share the same orbit. Brosch says this demonstrates that they come from the same original asteroid source.

Looking into the light

During the course of the study, Polishook and an international group of astronomers studied thirty-five asteroid pairs. Traditionally, measuring bodies in the solar system involves studying photographic images. The small size and extreme distance of the asteroids forced researchers to measure these pairs in an innovative way.

Instead, researchers measured the light reflected from each member of the asteroid pairs. The results proved that in each asteroid pair, one body was formed from the other. The smaller asteroid, he explains, was always less than forty percent of the size of the bigger asteroid. These findings fit precisely into a theory developed at the University of Colorado at Boulder, which concluded that no more than forty percent of the original asteroid can split off.

With this study, says Brosch, researchers have been able to prove the connection between two separate spinning asteroids and demonstrate the existence of asteroids that exist in paired relationships.