Aging irises would hobble biometric identity checks based on iris recognition

Confirming someone;s identity through iris recognition involves matching a new scan of their iris — done, say, at an airport check point — against templates in a library. The systems are designed to cope with the fact that the scanning process is slightly variable, so two scans of the same eye will be slightly different; researchers have evidence that the degree of difference between any two scans — called the Hamming distance — increases over time for scans of the same eye

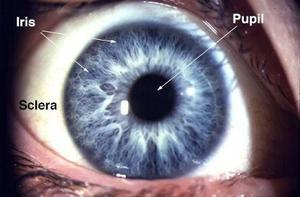

Each iris has unique properties, dimensions and patterning // Source: bioconsulting.com

The argument is being made that biometric traits are not only unique, bur are also for life. It appears that at least with regard to iris recognition, this is not the case. Iris scans can produce subtly different patterns over time, so the older the image of a person’s iris stored on a computer, the more likely that the system will fail to match it to a new scan of their iris.

Duncan Graham-Rowe writes that iris recognition systems work by scanning a person’s eye to create a digital representation or “template” of the texture of the iris. Confirming someone’s identity then becomes a matter of matching a new scan of their iris against templates in a library.

The systems are designed to cope with the fact that the scanning process is slightly variable, so two scans of the same eye will be slightly different. The degree of difference between any two scans is described by a parameter called the Hamming distance, which is small if the scans are of the same eye. As the Hamming distance increases, so too does the probability that the scans are of different irises.

Now Kevin Bowyer at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana and colleagues say they have evidence that the Hamming distance increases over time for scans of the same eye. They initially compared pairs of scans of twenty-six irises taken two months apart with scans made four years apart. The team measured an increase of 0.018 percent over the period. This translates directly into an increase in the false rejection rate: the rate at which an iris scan is not matched with its template. A system with a false rejection rate of 1 in 100, say, using scans made two months apart would produce 1.75 false rejections in 100 scans after four years, says Bowyer. That could be problematic in places such as India, which is considering storing iris scans in chips used in its national identity cards.

Bowyer presented the initial findings at the Identity in the Information Society workshop in London last year. He has just submitted the results of further work, including analysis of more irises, for publication.