Climate conundrumCivil wars in Africa have no link to climate change

Some researchers have argued that environmental variability and shocks, such as drought and prolonged heat waves, drive civil wars in Africa; a new paper investigates the empirical foundation for the claimed relationship in detail, and concludes that climate variability is a poor predictor of armed conflict; instead, African civil wars can be explained by generic structural and contextual conditions: prevalent ethno-political exclusion, poor national economy, and the collapse of the cold war system

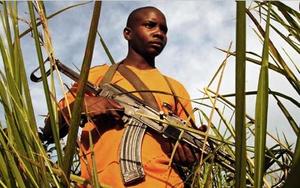

Child soldier in the Congo // Source: telegraph.co.uk

The idea that global warming will increase the incidence of civil conflict in Africa is wrong, according to a new study. What is more, the researchers who previously made the claim now concede that civil conflict has been on the wane in Africa since 2002, as prosperity has increased. If the trend continues, a more peaceful future may be in store.

A link between climate change and conflict was discovered last year, when a team led by Marshall Burke of the University of California at Berkeley and David Lobell of Stanford University, also in California, found a correlation between the incidence of civil wars in sub-Saharan Africa between 1981 and 2002 and spikes in temperature in the countries concerned (“Climate change will lead to more wars and deaths in Africa,” 24 November 2009 HSNW). They concluded that if temperatures kept rising, the number of conflicts would increase by more than 50 percent by 2030.

Peter Aldhous writes that now, Halvard Buhaug of the Peace Research Institute Oslo in Norway is taking Burke and Lobell to task over the methods and data they used. In particular, Buhaug argues that the researchers’ definition of conflict is misleading: they say a civil war has occurred if more than 1,000 people died in intra-national conflict in a year. “This is an arbitrary threshold,” Buhaug argues. “I think it’s better to focus on the onset of violence.”

Buhaug’s study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, as was the original study by Burke and Lobell.

When Buhaug looked at the initial outbreak of hostilities for conflicts in which more than 25 people perished in a year, he could find no significant association with high temperatures. He also points out that the incidence and severity of civil war in African countries has fallen since 2002.

Aldhous, following Buhaug, notes that the reasons for this are unclear, but between 2003 and 2008, overall GDP in Africa grew at a rate six times as high as in the preceding two decades, while many countries saw greater political stability. This suggests that sub-Saharan Africa may benefit more from economic and political development rather than policies to mitigate climate change.

Buhaug’s paper concludes that climate variability is a poor predictor of armed conflict. Instead, African civil wars can be explained by generic structural and contextual conditions: prevalent ethno-political exclusion, poor national economy, and the collapse of the cold war system.

“We’re trying to disentangle this,” says Burke. He and Lobell have reworked their calculations with climate data extending to 2008 and found that the relationship with temperature disappears. “We hope there has been a fundamental shift and that our earlier results are wrong.”

—Read more in Halvard Buhaug, “Climate not to blame for African civil wars,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 10 September 2010 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1005739107)