Nuclear wasteGlass offers a better way of storing U.K. nuclear waste

Researchers have shown, for the first time, that a method of storing nuclear waste normally used only for High Level Waste (HLW) could provide a safer, more efficient, and potentially cheaper solution for the storage and ultimate disposal of Intermediate Level Waste (ILW)

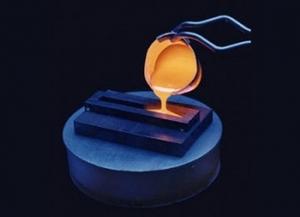

Storing waste in glass offers stability of storage containment // Source: exdat.com

University of Sheffield researchers have shown, for the first time, that a method of storing nuclear waste normally used only for High Level Waste (HLW), could provide a safer, more efficient, and potentially cheaper solution for the storage and ultimate disposal of Intermediate Level Waste (ILW).

A University of Sheffield release reports that ILW makes up more than three quarters of the volume of material destined for geological disposal in the United Kingdom.

Currently the U.K. preferred method is to encapsulate ILW in specially formulated cement. The waste is mixed with cement and sealed in steel drums, in preparation for disposal deep underground.

Two studies, published in the latest issues of Glass Technology - European Journal of Glass Science and Technology and the Journal of Nuclear Materials show that turning this kind of waste into glass, a process called vitrification, could be a better method for its long-term storage, transport and eventual disposal.

HLW is already processed using this technology which reduces both the reactivity and the volume of the waste produced. Until now, this method has not been considered suitable for ILW because the technology was not developed to handle large quantities of waste composed from a variety of different materials.

The research program, funded by the U.K. Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) and led by Professor Neil Hyatt in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at the University of Sheffield, tested simulated radioactive waste materials — those with the same chemical and physical makeup, but with non-radioactive isotopes — to produce glass and assess its suitability for storing lower grades of nuclear waste.

The process used to produce the glass waste storage packages is straightforward: the waste is dried, mixed with glass forming materials such as iron oxide or sodium carbonate, heated to make glass and finally poured into a container. For certain wastes — for example radioactively contaminated sand — the waste is actually used in the glass-making process.

A key discovery made by the Sheffield team was that the glasses produced for ILW proved to be very resistant to damage by energetic gamma rays, produced from the decay of radioactive materials.

“We found that gamma irradiation produced no change in the physical properties of these glasses, and no evidence that the residual radiation caused defects,” said Hyatt. “We think this is due to the presence of iron in the glass, which helps heal any defects so they cannot damage the material.

“For large volumes of waste that need to be stored securely, then transported to and eventually disposed of, vitrification could offer improved safety and cost effectiveness,” explains Hyatt.

Dr. Darrell Morris, research manager at NDA, said: “We welcome this fundamental research demonstrating a possible alternative means of treating ILW. We look forward to seeing further progress on the applicability of this technology to the U.K.’s waste inventory.”

— Read more in P. A. Bingham, “Vitrification of UK intermediate level radioactive wastes arising from site decommissioning: property modelling and selection of candidate host glass compositions,” Glass Technology - European Journal of Glass Science and Technology 53, no. 3, Pt. A (June 2012): 83-100; and O. J. McGann et al., “The effects of γ-radiation on model vitreous wasteforms intended for the disposal of intermediate and high level radioactive wastes in the United Kingdom,” Journal of Nuclear Materials (21 April 2012) (doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2012.04.007)