BioterrorismDHS using Boston subway system to test new sensors for biological agents

Bioterrorism is nothing new, and although medicines have made the world a safer place against a myriad of old scourges both natural and manmade, it still remains all too easy today to uncork a dangerous cloud of germs; DHS’s Science and Technology Directorate (DHS S&T) has scheduled a series of tests in the Boston subways to measure the real-world performance of new sensors recently developed to detect biological agents

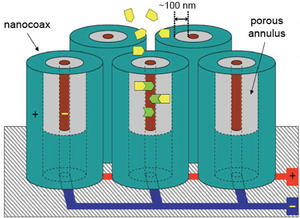

Schematic of one type of sensor device // Source: nanowerk.com

The idea that disease and infection might be used as weapons is truly dreadful, but there is plenty of evidence showing that biological weapons have been around since ancient times.

Bioterrorism is nothing new, and although medicines have made the world a safer place against a myriad of old scourges both natural and manmade, it still remains all too easy today to uncork a nasty cloud of germs. DHS’s Science and Technology Directorate (DHS S&T) has scheduled a series of tests in the Boston subways to measure the real-world performance of new sensors recently developed to detect biological agents.

DHS says that S&T’s Detect-to-Protect (D2P) Bio Detection project is assessing several sensors (made by Flir Inc., Northrop Grumman, Menon and Associates, and Qinetiq North America) to alert authorities to the presence of biological material. These devices with “trigger” and “confirmer” sensors have been designed to identify and confirm the release of biological agents within minutes.

In 2009 and in early August this year, inert gasses were released in the Boston subway system in an initial study to determine where and how released particulates would travel through the subway network and to identify exactly where to place these new sensors.

The current study will involve the release of a small amount of an innocuous killed bacterium in subway stations in the Boston area to test how well the sensors work. After the subway stations close, S&T scientists will spray small quantities of killed Bacillus subtilis in the subway tunnels. This common, food-grade bacterium is found everywhere in soil, water, air, and decomposing plant matter and, even when living, is considered nontoxic to humans, animals, and plants.

S&T’s Dr. Anne Hultgren, manager of the D2P project, says, “While there is no known threat of a biological attack on subway systems in the United States, the S&T testing will help determine whether the new sensors can quickly detect biological agents in order to trigger a public safety response as quickly as possible.”

DHS notes that it leads federal efforts to prepare for, respond to, and recover from a possible domestic biological attack. The testing will continue periodically for the next six months and will be monitored by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority as well as state and local public health officials. The particles released in the stations will dissipate quickly. Before they do, however, their brief travels will provide invaluable data for DHS’ ongoing effort to protect American travelers from potential hazards.