Missile defenseSerious limitations make boost-phase missile interception impractical

One of the central elements of President Reagan’s 1983 “Star Wars” ballistic missile defense initiative was boost-phase defense: boost-phase defense systems are intended to shoot down enemy missiles immediately following launch while the rocket engine is still firing; a new congressionally mandated study by the National Research Council study says that to defend against ballistic missile attacks more effectively, the United States should concentrate on defense systems that intercept enemy missiles in midcourse and stop spending money on boost-phase defense systems of any kind

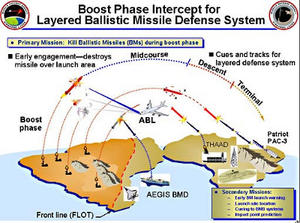

Schematic of boost-phase ballistic missile interception // Source: albasalh.com

To defend against ballistic missile attacks more effectively, the United States should concentrate on defense systems that intercept enemy missiles in midcourse and stop spending money on boost-phase defense systems of any kind, concludes a new, congressionally mandated report from a committee of the National Research Council. A National Academies release reports that the committee was asked to assess the feasibility, practicality, and affordability of U.S. boost-phase missile defenses and compare them with other alternatives for countering limited nuclear or conventional ballistic missile attacks by regional actors such as Iran or North Korea.

Boost-phase defense systems are intended to shoot down enemy missiles immediately following launch while the rocket engine is still firing. These systems are theoretically possible, but they are not “practical or feasible” because they would have only a few minutes in which to intercept enemy missiles during the boost phase and air- or ground-based systems generally cannot be located close enough to potential threats to be effective. Space-based boost-phase interceptors would require hundreds of satellites and cost as much as $500 billion to acquire and operate over a 20-year span — at least ten times as much as any other approach, the committee estimated.

Any practical missile defense system, the committee concluded, must rely primarily on intercepting enemy missiles in midcourse, which can and should provide the most effective ballistic missile defense of the U.S. homeland. Midcourse defense provides more battle space for multiple opportunities to identify and shoot down targets. Currently, the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system, which deploys thirty ground-based midcourse interceptors at Fort Greely in Alaska and Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, provides an “early but fragile” U.S. homeland defense capability for a potential threat from North Korea, the report says. The GMD, however, has “shortcomings” and limited ability to defend the United States from missiles launched by countries other than North Korea, and the Missile Defense Agency’s currently planned improvements will not adequately address these.

To overcome these shortcomings, the committee recommended adding a third interceptor site to the U.S. northeast and several technical fixes to make the GMD both more effective and less expensive.

These fixes include developing smaller, but more capable interceptor missiles using tested technologies and employing a suite of proven X-band radar components at five existing early-warning radar sites. These radars, combined with infrared sensors aboard the interceptors, would provide much more time and data for identifying