Islamic fundamentalismWest Africa expert still hopes Mali would not devolve into “Africanistan”

Earlier this summer, Islamic militants in the West African nation of Mali destroyed the tombs of Sufi Muslim saints in the fabled city of Timbuktu; the act, widely compared to the Taliban’s destruction of colossal stone Buddhas in Afghanistan, raised concerns about the fate of other cultural treasures in what was once a vibrant center of Islamic scholarship

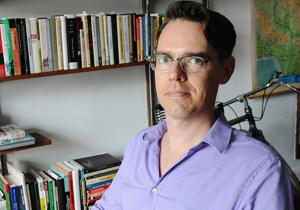

Columbia University's Gregory Mann has been raising the alarm about Ansar Dine and the radicalization of the Northern Mali // Source: columbia.edu

Earlier this summer, Islamic militants in the West African nation of Mali destroyed the tombs of Sufi Muslim saints in the fabled city of Timbuktu.

The act, widely compared to the Taliban’s destruction of colossal stone Buddhas in Afghanistan, raised concerns about the fate of other cultural treasures in what was once a vibrant center of Islamic scholarship.

A Columbia University release reports that among those monitoring the chaotic situation is Gregory Mann, an associate professor of history who has been traveling to and writing about the former French colony for more than fifteen years.

His first book, Native Sons: West African Veterans and France in the Twentieth Century, won the David H. Pinkney Prize for best book in French history in 2006.

Closer to home, Mann serves as an expert in asylum cases involving West Africans in New York. “If I can help someone in a difficult situation, it’s just the right thing to do,” says Mann.

Until recently, Mali had been a relatively stable democracy in a turbulent part of the world, with free speech, a free press and regular elections. In March, the military, angered by a lack of government support in fighting separatists in northern Mali, launched a coup.

The fighting between the military and the government emboldened the two main groups battling for control in the north — the separatist MNLA and the Islamic militants of Ansar Dine. Both groups had gotten stronger after the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi as heavily armed Malian fighters who worked in Qaddafi’s army came home.

“The NATO intervention in Libya didn’t cause the current conflict in Mali, but there is no question it accelerated it,” Mann says.

Ansar Dine, which seeks to impose Sharia law in Mali, quickly gained the upper hand and now controls the north, more than half the nation’s territory.

Some leaders in neighboring countries are calling Mali “Africanistan,” a reference to Afghanistan.

Although Mann sees similarities between Ansar Dine and the al Qaeda-backed Taliban, he rejects the comparison between the two nations. “Islam is practiced very differently in Mali than in Afghanistan,” says Mann. “In Mali, the faith is practiced with a substantial dose of tolerance and gender relations are more equitable. So it is not surprising that Ansar Dine has found little popular support with most Malians.”

The release notes that according to Amnesty International, Ansar Dine has beaten and killed residents of the north for not following what it considers appropriate Islamic behavior. It forbids reading books or playing music it deems contrary to Islam. Women are forced to cover their heads and legs in public. In some areas, it has closed schools to prevent the mixing of boys and girls. In July, Islamic militants allied with Ansar Dine stoned to death a man and a woman they accused of having children outside of marriage.

Mann says the destruction of the tombs was meant to attack the ideas of Sufism, a mystical tradition in Islam widely practiced across Mali but unacceptable to Ansar Dine.

Now he is concerned about the possible destruction of Islamic manuscripts in Timbuktu. “No one has plumbed the depths of those texts, perhaps the most important historical documents telling the story of West Africa — including Islamic doctrine, slavery, marriage, trade, geography, and science. If those documents are destroyed, that knowledge might be gone forever.”

In the past six months, more than 400,000 people have fled northern Mali, a vast region of the Sahara Desert about the size of France. Mann fears the country may be entering a long period of instability and lawlessness.

“My hope is that the democratic political traditions and moderate religious traditions will help peace-seeking Malians reclaim their country,” he says. “But I don’t see that happening in the near term.”

Last year, working with a colleague at the University of Bamako, the capital of Mali, Mann ran a program pairing Malian graduate students with their counterparts at Columbia to study Malian immigration in New York. “We had hoped to run a similar program in Mali in 2013, but our ability to do that is now very much in doubt,” he says.