FrackingBacteria to clean contaminated leftover water used in fracking

Fracking is a drilling technique which uses lots of water — up to 5-7 million gallons per frack. One well may be fracked several times. The water goes in clean and comes out contaminated with organic substances that render it unfit for reuse. Purifying that water would reduce the pressure on waste disposal sites called injection wells, as well as on sites of wastewater spills. Researchers say that bacteria may someday clean leftover frack water.

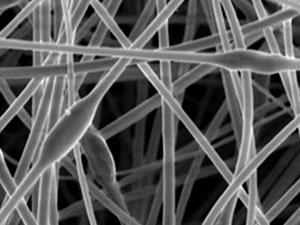

Swollen sections of fibers are packed with oil-eating bacteria // Source: umn.edu

In humans’ eternal quest for more energy, a relatively new oil and natural gas mining technique targets deposits locked in pockets of rock.

Called hydrofracturing, or fracking, the technique uses lots of water, which goes in clean and comes out contaminated with organic substances that render it unfit for reuse. Purifying that water would reduce the pressure on waste disposal sites called injection wells, as well as on sites of wastewater spills.

A University of Minnesota release reports that working toward that goal are University of Minnesota microbiologists Larry Wackett and Michael Sadowsky, who have already pioneered the use of pollutant-eating bacteria against soil contamination.

Along with mechanical engineering professor Alptekin Aksan, Wackett and Sadowsky are developing a silica sponge stuffed with oil-eating bacteria. The researchers and College of Biological Sciences dean Robert Elde, whose role is to help commercialize the work, are funded by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant.

Here is a glimpse of the problem and the potential solution.

Fracking 101

Fracking helps drillers reach pockets of oil and gas trapped in bubbles within impermeable rock, says UM earth sciences professor E. Calvin Alexander Jr., an expert on how water moves through rock.

“Oil companies figured out they could ‘fracture’ rock with high-pressure fluids that lifted and broke the rock,” he says. “This could be done in horizontal wells extending thousands of feet. Then to get the oil [or gas] out, they reduced the pressure.”

It was not that simple, however, because reducing the pressure allows the rock to fall back in place, closing the new fractures and blocking the flow of oil or gas. So drillers inject sand to hold the spaces in the rock open. The porous sand allows oil and gas to flow, and cocktails of organic chemicals, including soaps, are injected to lubricate the sand so it can get into cracks.

Reducing the pressure, however, sends some of the injected fluid – water — gushing out again.

Trouble is, “it comes out with salt and other buried ugly stuff, like heavy metals, in addition to the oil or gas,” says Alexander. “The secondary flowback water, [now contaminated with] the chemicals they put in to lubricate the sand, creates waste.”

How much water is involved? Wackett says he has seen up to 5-7 million gallons per frack, and one well may be fracked several times. To put it in perspective, the annual water use is about 2 percent of the amount used in agriculture, he