Predictive policingMore police departments adopt predictive policing

More police departments have adopted data analytics as a way to combat urban crime. Supporters of the approach, also referred to as predictive policing, say that if it is used in conjunction with existing policing techniques, such as community policing, it could have a drastic impact on crime. Some note, however, that the predictive policing methodology is more useful for its general tactical utility rather than the accuracy of its predictions.

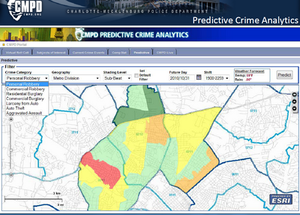

Analytics allow police to concentrate on likely crime areas // Source: techbang.com

William Bratton, head of New York City’s police department, is credited with introducing data analytics as a way to combat crime in American cities during his time as chief of police in Los Angeles between 2002 and 2009. By 2011, Los Angeles police had used predictive analysis to reduce property crime by 12 percent in one neighborhood. If used in conjunction with existing policing techniques, such as community policing, predictive policing could have a drastic impact on crime, Bratton once said.

Today, statistical data and analytics software are being used with license plate readers (LPRs) to help law enforcement predict where a crime is going to happen, and who the culprits are likely to be. According to Government Technology, some analysts argue that humans who commit crimes are too random, but evidence from cities across the United States reflects patterns in how and when crimes are committed. With predictive policing, law enforcement can direct their already limited resources and manpower to vulnerable neighborhoods.

“Predictive policing is another extremely popular technology when you have limited resources,” said Jim Bueermann, president of the Police Foundation. “It becomes extremely valuable when you can predict where to put your resources to be the most valuable and effective.”

Predictive policing can be ineffective when data accuracy is emphasized over tactical utility, law enforcement agencies misunderstand the factors contributing to a prediction, and when civil and privacy rights are overlooked. “The idea that you can forecast where the highest probability of crime will occur — it’s never going to be an exact prediction, only a target for a future hot spot, that’s all,” Bueermann said.

Within the past decade, several U.S. police departments have adopted LPRs to identify vehicles near crime scenes, and to track stolen vehicles and citizens with outstanding warrants. The plate readers provide geographic and time information, and according to the Rand Corporation’s 2013 study on predictive policing, law enforcement agencies are using LPRs to predict where certain crimes are likely to occur based on the crime records of drivers at certain locations. New York City has used LPRs since 2006 and has increased arrests for grand larceny by 31 percent, while recovering more than 3,600 vehicles. While LPRs are expensive for small municipalities, the $25,000 (mobile) to $100,000 (fixed) per unit devices can generate revenue as police departments track vehicles with outstanding driving or parking citations. As more cities adopt LPRs, privacy concerns have been the topic of discussion. Some police departments keep data from LPRs for up to two years, and some require data to be deleted if found no longer of use to an investigation.