ResilienceEngineers build, test earthquake-resistant house

Residential homes already do a good job of keeping the people inside safe when a temblor hits. Earthquakes, however, typically do a lot of minor structural damage. For example, after the 1994 Northridge quake, the majority of the $25.6 billion in repair costs paid for fixes to 500,000 residential structures. Most of those homes were not destroyed, but nonetheless thousands of families had to find a new place to live while their houses were repaired. Twenty-five years after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, Stanford engineers have built and tested an earthquake-resistant house that stayed staunchly upright even as it shook at three times the intensity of that destructive temblor. The engineers developed inexpensive design modifications that could be incorporated into new homes to reduce damage in an earthquake.

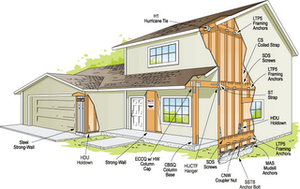

One design for quake-proof residence // Source: eduzones.com

Stanford engineers have built and tested an earthquake-resistant house that stayed staunchly upright even as it shook at three times the intensity of the destructive 1989 Loma Prieta temblor twenty-five years ago.

The engineers outfitted their scaled-down, boxy two-story house with sliding “isolators” so it skated along the trembling ground instead of collapsing. A Stanford University release reports that they also including extra-strength walls, to create a home that might replace the need for residential earthquake insurance, said project leader Gregory Deierlein, Stanford’s John A. Blume Professor in the School of Engineering.

The modifications are inexpensive and could be incorporated into new homes as soon as designers and contractors decide to try them, according to the researchers.

“We want a house that is damage free after the big earthquake,” said Eduardo Miranda, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering. He co-led the project with Deierlein and Benjamin Fell, an associate professor in the Department of Civil Engineering at California State University, Sacramento.

Residential homes already do a good job of keeping the people inside safe when a temblor hits. Earthquakes, however, typically do a lot of minor structural damage. For example, after the 1994 Northridge quake, the majority of the $25.6 billion in repair costs paid for fixes to 500,000 residential structures.

Most of those homes were not destroyed, but nonetheless thousands of families had to find a new place to live while their houses were repaired. Even if the walls stay up in a quake, wall finishes like drywall and stucco, along with architectural fixtures like cabinetry, are damaged because of the large sideways movements caused by earthquakes, Deierlein said.

The house that Stanford built had two major modifications to stave off earthquake damage. For one, it was not affixed into a foundation, but rested on a dozen steel-and-plastic sliders, each about 4.5 inches in diameter. Under those sliders were either plates or bowl-shaped dishes made of galvanized steel. These units are called seismic isolators.

“The idea of seismic isolation is to isolate the house from the vibration of the ground,” Miranda said. “When the ground is moving, the house will just slide.” Seismic isolators already protect large structures like San Francisco City Hall and structures at San Francisco International Airport, Deierlein said, but they are quite expensive. He and his team adapted the technology for residential use by incorporating inexpensive materials into their scaled-down isolators.