CrimePredictive policing substantially reduces crime in Los Angeles during 21-month period

Can math help keep our streets safer? A new study by a UCLA-led team of scholars and law enforcement officials suggests the answer is yes. A mathematical model they devised to guide where the Los Angeles Police Department should deploy officers, led to substantially lower crime rates during a recent 21-month period. The model was so successful that the LAPD has adopted it for use in 14 of its 21 divisions, up from three in 2013.

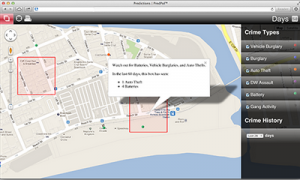

Model predicts and prevents crime // Source: fbi.gov

Can math help keep our streets safer?

A new study by a UCLA-led team of scholars and law enforcement officials suggests the answer is yes. A mathematical model they devised to guide where the Los Angeles Police Department should deploy officers, led to substantially lower crime rates during a recent 21-month period.

“Not only did the model predict twice as much crime as trained crime analysts predicted, but it also prevented twice as much crime,” said Jeffrey Brantingham, a UCLA professor of anthropology and senior author of the study. A paper about the work, which was also tested in Kent, England, was published online today by the Journal of the American Statistical Association.

UCLA reports that the model was so successful that the LAPD has adopted it for use in 14 of its 21 divisions, up from three in 2013.

Developed using six years of mathematical research and a decade of police crime data, the program predicts times and places that serious crimes will occur based on historical crime data in a given area. A key to its success, Brantingham said, is that the algorithm behind the model effectively “learns” over time.

“In much the same way that your video streaming service knows what movie you’re going to watch tomorrow, even if your tastes have changed, our algorithm is constantly evolving and adapting to new crime data,” he said.

Beginning in 2011, the researchers analyzed crime trends in the LAPD’s Southwest division and in two Kent divisions to determine whether their model could predict, in real time, when and where major crimes would occur. Their analysis in Los Angeles focused on burglaries, theft from cars and theft of cars. In Kent, they studied patterns for those crimes as well as violent crimes including assault and robbery.

The researchers tested the computer model by pitting it against professional crime analysts, seeing which could more accurately predict where crimes would occur. On each of 117 days in Los Angeles, they gave the human analysts a map of the entire police district and asked them to identify one precise location — only about half-a-block in size — where a crime would be most likely to occur within a specific 12-hour period. The algorithm was programmed to answer the same question (in this phase of the experiment, police officers did not act on the model’s predictions).