Emerging threatsGlobal learning required to prevent carbon capture, storage from being abandoned

Governments should not be abandoning carbon capture and storage, argues a Cambridge researcher, as it is the only realistic way of dramatically reducing carbon emissions. Instead, they should be investing in global approaches to learn what works – and what doesn’t.

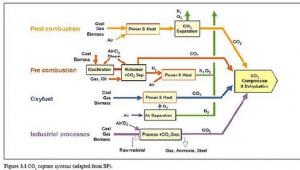

Schematic of CCS process // Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Carbon capture and storage, which is considered by many experts as the only realistic way dramatically to reduce carbon emissions in an affordable way, has fallen out of favor with private and public sector funders. Corporations and governments worldwide, including most recently the United Kingdom, are abandoning the same technology they championed just a few years ago.

U Cambridge reports that in a commentary published 11 January in the inaugural issue of the journal Nature Energy, a University of Cambridge researcher argues that now is not the time for governments to drop carbon capture and storage (CCS). Like many new technologies, it is only possible to learn what works and what doesn’t by building and testing demonstration projects at scale, and that by giving up on CCS instead of working together to develop a global portfolio of projects, countries are turning their backs on a key part of a low-carbon future.

CCS works by separating the carbon dioxide emitted by coal and gas power plants, transporting it, and then storing it underground so that the CO2 cannot escape into the atmosphere. Critically, CCS can also be used in industrial processes, such as chemical, steel, or cement plants, and is often the only feasible way of reducing emissions at these facilities. While renewable forms of energy, such as solar or wind, are important to reducing emissions, until there are dramatic advances in battery technology, CCS will be essential to deliver flexible power and to build green industrial clusters.

“If we’re serious about meeting aggressive national or global emissions targets, the only way to do it affordably is with CCS,” said Dr. David Reiner of Cambridge Judge Business School, the paper’s author. “But since 2008, we’ve seen a decline in interest in CCS, which has essentially been in lock step with our declining interest in doing anything serious about climate change.”

Just days before last year’s UN climate summit in Paris, the U.K. government cancelled a four-year, £1 billion competition to support large-scale CCS demonstration projects. And since the financial crisis of 2008, projects in the United States, Canada, Australia, Europe, and elsewhere have been cancelled, although the first few large-scale integrated projects have recently begun operation. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says that without CCS, the costs associated with slowing global warming will double.