ZikaIn Zika, echoes of U.S. rubella outbreak of 1964-65

Just over fifty years ago, a highly contagious but seemingly harmless virus swept through the United States, infecting as many as 12.5 million people. In both adults and children, the virus presented as a mild illness, but caused birth defects in some babies born to women who were infected while pregnant. Does this sound familiar? Though separated by time and place, there are surprising similarities in the social issues raised by the rubella outbreak of 1964-65 and the recent Zika outbreak in South America. Both viruses can cause birth defects, a fact that ties them to social issues surrounding pregnancy, women’s health, and the politics of abortion.

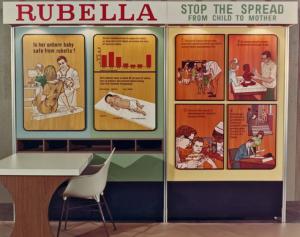

A display used to educate the public on rubella vaccination // Source: theconversation.com

Just over fifty years ago, a highly contagious but seemingly harmless virus swept through the United States, infecting as many as 12.5 million people. In both adults and children, the virus presented as a mild illness, but caused birth defects in some babies born to women who were infected while pregnant. Does this sound familiar? Though separated by time and place, there are surprising similarities in the social issues raised by the rubella outbreak of 1964-65 and the recent Zika outbreak in South America.

Both viruses can cause birth defects, a fact that ties them to social issues surrounding pregnancy, women’s health, and the politics of abortion.

The rubella epidemic, with an estimated 20,000 affected newborns, changed medical and public consciousness about the virus. Some have recently argued that it even changed ideas about abortion.

As a sociologist who studies medicine and science, I am interested in understanding the narratives we develop about disease. I examined the rubella outbreak in my 2008 book, The Vaccine Narrative, and how perceptions of the disease interacted with stories about vaccination.

Unlike other vaccines, the rubella vaccine conferred no direct benefits to recipients. Instead, it promised to prevent possible future birth defects and to reduce rubella-related abortions; for rubella vaccine, the health of the woman mattered almost entirely in terms of her status as a potential mother.

The rubella outbreak of 1964-65 – and access to abortion

In the spring of 1964, doctors in North America confirmed that the deafness and blinding cataracts they found in massive numbers of children had been caused by rubella.