ResilienceResilience and adaptation strategies can address the impacts of climate change

By the end of this century, Chicago could face the kind of searing summer heat that Las Vegas sees now. Phoenix could hit 110 degrees, 60 or more days a year. That’s not wild speculation. It’s the official position of 13 federal agencies on climate change, released late last year with a warning: Local governments need to do more to prepare. Every road they build, every storm drain they put in, will have to hold up under conditions that modern civilization has never seen. How do you plan for that? Researchers at RAND have been working on that problem for a while now.

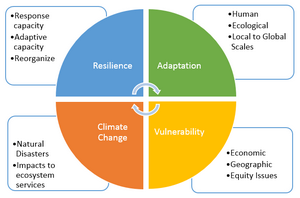

Climate Resilience Model // Source: commons.wikimedia.org

By the end of this century, Chicago could face the kind of searing summer heat that Las Vegas sees now. Phoenix could hit 110 degrees, 60 or more days a year.

That’s not wild speculation. It’s the official position of 13 federal agencies on climate change, released late last year with a warning: Local governments need to do more to prepare. Every road they build, every storm drain they put in, will have to hold up under conditions that modern civilization has never seen.

How do you plan for that? Researchers at RAND have been working on that problem for years now. Their solution: Don’t try to guess what the future might bring; imagine an entire range of possible futures, and then look for solutions that work regardless of which one comes to pass. If that sounds complicated, it is. So for now, just consider the Pittsburgh sewer system.

Anticipate new climate threats and impacts

Lisa Werder Brown begins her kayak tours of Pittsburgh rivers with a safety briefing: Don’t touch your face. Keep your hand sanitizer close. And take a good shower when you get home. She’s the executive director of Watersheds of South Pittsburgh, and if someone can flush something down the toilet, she’s seen it in the rivers. “We get a little bit of rain,” she says, “and it just comes gushing out.”

Like many older American cities, Pittsburgh relies on a combined sewer-stormwater system that was state of the art about a century ago. Today, it is old, leaky, and so overwhelmed that it overflows almost every time it rains, sending a mixture of raw sewage and stormwater into the rivers. The region is under a federal mandate to address the problem, a project that will likely cost billions of dollars.

In the past, engineers would have looked to the historical record to figure out how much capacity they needed to build into the system. They would have calculated annual rainfall averages, made note of what a 100-year storm could do, and planned accordingly. That doesn’t work anymore.