Planetary securityCelestial menace: Defending Earth from asteroids

Incoming asteroids have been scarring our home planet for billions of years. This month humankind left our own mark on an asteroid for the first time: Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft dropped a copper projectile at very high speed in an attempt to form a crater on asteroid Ryugu. A much bigger asteroid impact is planned for the coming decade, involving an international double-spacecraft mission.

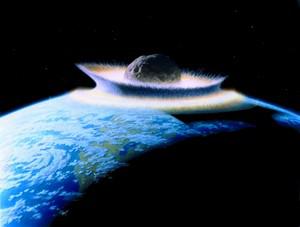

Rendering of a collision between earth and planetoid // Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Incoming asteroids have been scarring our home planet for billions of years. This month humankind left our own mark on an asteroid for the first time: Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft dropped a copper projectile at very high speed in an attempt to form a crater on asteroid Ryugu. A much bigger asteroid impact is planned for the coming decade, involving an international double-spacecraft mission.

On 5 April, Hayabusa2 released an experiment called the ‘Small Carry-on Impactor’ or SCI for short, carrying a plastic explosive charge that shot a 2.5-kg copper projectile at the surface of the 900-m diameter Ryugu asteroid at a velocity of around 2 km per second. The objective is to uncover subsurface material to be brought back to Earth for detailed analysis.

“We are expecting it to form a distinctive crater,” comments Patrick Michel, CNRS Director of Research of France’s Côte d’Azur Observatory, serving as co-investigator and interdisciplinary scientist on the Japanese mission. “But we don’t know for sure yet, because Hayabusa2 was moved around to the other side of Ryugu, for maximum safety.

“The asteroid’s low gravity means it has an escape velocity of a few tens of centimetres per second, so most of the material ejected by the impact would have gone straight out to space. But at the same time it is possible that lower-velocity ejecta might have gone into orbit around Ryugu and might pose a danger to the Hayabusa2 spacecraft.

“So the plan is to wait until this Thursday, 25 April, to go back and image the crater. We expect that very small fragments will meanwhile have their orbits disrupted by solar radiation pressure – the slow but persistent push of sunlight itself. In the meantime we’ve also been downloading images from a camera called DCAM3 that accompanied the SCI payload to see if it caught a glimpse of the crater and the early ejecta evolution.”