Search and rescueRobot swarm to aid rescue teams

A new system of autonomous flying robots being developed at the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) could establish wireless communication networks to aid rescue teams in the event of a disaster

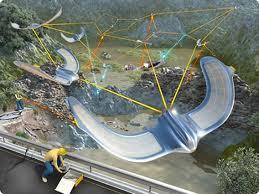

SMAVNET drones deployed // Source: singularityhub.com

A new system of autonomous flying robots being developed at the Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) could establish wireless communication networks to aid rescue teams in the event of a disaster.

The Swarming Micro Air Vehicle Network (SMAVNET) research project at EPFL’s Laboratory of Intelligent Systems (LIS) was set up to study swarm intelligence, the science of artificially mimicking the efficient collective behaviors of animal or insect colonies. The aim is to create a system which could be deployed in disaster scenarios says Jean-Christophe Zufferey, a research scientist at LIS. “We started doing research at EPFL on bio-inspired robots in 2001, beginning with a fly-inspired artificial insect that could avoid hitting the walls and ground. From that success we moved on to test these outdoors,” Zufferey said.

This led to the creation of a “flying wing,” one of 10 devices which have flown together as part of the SMAVNET project.

Made from lightweight plastic foam with a lithium battery-powered electric motor at the rear, these Micro Air Vehicles (MAVs) are launched a bit like you would a Frisbee. Once airborne, an autopilot controls altitude, air speed, and turn rate, while the MAVs avoid mid-air collisions by communicating with one another via optical flow sensors.

These sensors are mounted at the front of each MAV, enabling it to detect the distance between objects and change direction if they get too close to each another.

“The sensors are similar to the ones found in a computer mouse — they are really good optical detectors,” Zufferey said.

LIS says the inspiration for the establishment and maintenance of the MAVs’ communication pathways between themselves and a base controller comes from army ants, which lay pheromone paths from their nests to food sources.

Final data for the SMAVNET project is currently being gathered before LIS researchers start on a follow-up project called “Swarmix” which will explore how these robot swarms can be applied to assist relief work in disaster zones.

The LIS team says the idea is for all MAVs in a swarm to be equipped with a small wireless module to form an ad-hoc network which rescue teams can use to communicate.

Small flying robots have obvious advantages over temporary land-based network devices, negating problems with difficult terrain and line-of-sight communication, and they do not rely on expensive sensors or radar equipment.

But there are important modifications that will need to be made to turn this research project into a product, Zufferey says.

The most obvious problem is endurance. Small MAVs are currently only capable of staying in the air for 30 to 60 minutes, he says, but solar technology could solve this in the near future.

And while the 420-gram drones, probably the lightest of their kind in the world, according to Zufferey, will not cause any damage should they crash into anything or anyone, their weight precludes flying in anything but moderate winds (15-20 mph) and weather.

But this has not stopped utilizing the current capabilities of a single MAV to set up a spin-off company, senseFly, which can be deployed for aerial photography, atmospheric sampling, surveillance, or 2D and 3Dmapping.

As for robot swarms, Zufferey says that they could be on the market in two to four years.