-

“Unprecedented” storms, floods in north-west England are more common than we think

The recent “unprecedented” flooding in north-west England might be more common than currently believed, a group of scientists has warned. A team of experts has drawn on historic records to build a clearer picture of the flooding. They conclude that twenty-first-century flood events such as Storm Desmond are not exceptional or unprecedented in terms of their frequency or magnitude, and that flood frequency and flood risk forecasts would be improved by including data from flood deposits dating back hundreds of years.

-

-

Nature influences water in the Colorado River basin more than humans do

Researchers have found that the water supply of the Colorado River basin, one of the most important sources for water in the southwestern United States, is influenced more by wet-dry periods than by human use, which has been fairly stable during the past few decades. The team found that water storage decreased by 50 to 100 cubic kilometers (enough water to fill Lake Mead as much as three times) during droughts that occur about every decade. The big difference between recent and previous droughts is that there have been few wet years since 2000 to replenish the water. In contrast, multiple wet years followed drought years in the 1980s and 1990s.

-

-

Climate outlook may be worse than feared

The impact of climate change may be worse than previously thought, a new study suggests. The research first created a simple algorithm to determine the key factors shaping climate change and then estimated their likely impact on the world’s land and ocean temperatures. The method is more direct and straightforward than that used by the IPCC, which uses sophisticated, but more opaque, computer models.

-

-

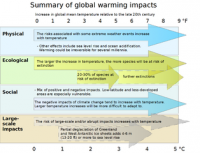

Climate change impacts may appear in some areas sooner than expected

Some impacts of global climate change will appear much sooner than others — with only moderate increases in global temperature. While rising sea levels may one day threaten the commuter tunnels and subway lines of New York City, it will have effects much sooner in other parts of the world – for example, the Marshall Islands and Bangladesh. In countries exposed to the destructive effects of climate change sooner rather than later, there will be little incentives to do something about climate change because the damage has already been done. Thus, once significant portions of the Marshall Islands or Bangladesh are destroyed by rising seas, the rate of damage will reach “saturation” — an inflection point beyond which further temperature increases have little additional effect. Once the Marshall Islands are large sections of Bangladesh are uninhabitable, there is not more damage that can be done there, and the governments of these countries will not have an incentive to participate in global climate efforts because they will not have anything more to lose.

-

-

Global freshwater loss due to dams, irrigation much larger than previously thought

Dams and irrigation, by increasing evapotranspiration, raise the global human consumption of freshwater to a much higher level than previously thought. This effect increases the loss of freshwater to the atmosphere and thereby reduces the water available for humans, societies and ecosystems on land.

-

-

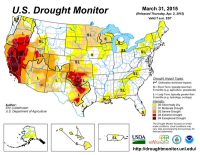

U.S. worsening droughts require alternative ways of protecting urban water supplies

In the American West, unprecedented droughts have caused extreme water shortages. The current drought in California and across the West is entering its fourth year, with precipitation and water storage reaching record low levels. Droughts are ranked second in the United States in terms of national weather-related economic impacts, with annual losses just shy of $9 billion. With water scarcity likely to increase due to advancing climate change, the economic and environmental impacts of drought are also likely to get worse. Alternative models of watershed protection that balance recreational use and land conservation must no longer be ignored to preserve water supplies against the effects of climate change, experts argue.

-

-

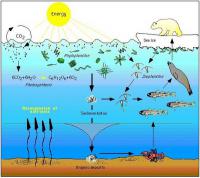

Global warming may affect oxygen-producing ocean phytoplankton

Past and current climate change has affected the food sources in the surface waters in the North Pacific Ocean. Climate change is predicted to alter marine phytoplankton (algae and diatoms) communities and affect productivity, biogeochemistry, and the efficacy of the biological pump. The slow global warming over the most recent approximate 150 years – roughly corresponding to the industrial revolution — has been beneficial, seeing an increase in nitrogen fixing cyanobacteria resulting in food production. “It’s sort of a carbon credit because the phytoplankton are making their own nitrogen-based fertilizer out of dissolved nitrogen,” says one researcher. But if global warming continues, the consequences may be dire. “This picoplankton community shift may have provided a negative feedback to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide, during the last 100 years. However, we cannot expect this to be the case in the future,” the researcher said.

-

-

Depletion of ocean phytoplankton could suffocate life on planet Earth

About two-thirds of the planet’s total atmospheric oxygen is produced by ocean phytoplankton — and therefore cessation would result in the depletion of atmospheric oxygen on a global scale, which could threaten the mortality of animals and humans.

-

-

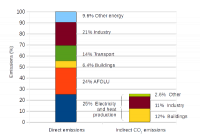

Coal plant plans could make it impossible to hold warming below 2°C

There are 2,440 planned coal plants around the world, totaling 1428GW, which could emit approximately 16-18 percent of the total allowed emissions in 2030 (under a 2°C-compatible scenario, medium range). If all coal plants in the pipeline were to be built, by 2030, emissions from coal power would be 400 percent higher than what is consistent with a 2°C pathway, according to a new analysis.

-

-

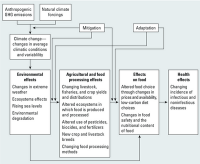

Climate change poses multiple threats to global food system

Climate change is likely to have far-reaching impacts on food security throughout the world, especially for the poor and those living in tropical regions, according to a new international report. The report warns that warmer temperatures and altered precipitation patterns can threaten food production, disrupt transportation systems, and degrade food safety, among other impacts. As a result, international progress in the past few decades toward improving food security will be difficult to maintain.

-

-

Social sciences are best hope for ending debates over climate change

The toxicity of the public debate in the United States over climate change is increasing, and to detoxify the debate, we need to understand the social forces at work. We must recognize that the public debate in the United States over climate change is not about carbon dioxide and greenhouse gas models; it is about opposing cultural values and worldviews through which that science is viewed. The opposing sides have less to do with the scientific basis of the issue and more to do with the ways in which people receive, assess, and act upon scientific information. To move forward, we have to disengage from fixed battle on one scientific front and seek approaches that engage people who are undecided about climate change on multiple social and cultural fronts. Only by broadening the scope of the debate to include this social and cultural complexity can we ever hope to achieve broad-scale social and political consensus. More scientific data can only take us so far; engaging the inherently human aspects of this debate will take us the rest of the way.

-

-

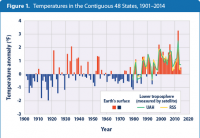

2015 likely to be warmest on record, 2011-2015 warmest 5-year period: WMO

The global average surface temperature in 2015 is likely to be the warmest on record and to reach the symbolic and significant milestone of 1° Celsius above the pre-industrial era, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The years 2011-2015 have been the warmest five-year period on record, with many extreme weather events — especially heatwaves — influenced by climate change. Levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere reached new highs, with global average concentration of CO2 crossed the 400 parts per million barrier for the first time. “This is all bad news for the planet. Greenhouse gas emissions, which are causing climate change, can be controlled. We have the knowledge and the tools to act. We have a choice. Future generations will not,” said WMO secretary-general Michel Jarraud.

-

-

Paris pledges, if implemented and followed, can avert severe climate change

More than 190 countries are meeting in Paris this week to create a durable framework for addressing climate change and to implement a process to reduce greenhouse gases over time. A key part of this agreement would be the pledges made by individual countries to reduce their emissions. Scientists say that if implemented and followed by measures of equal or greater ambition, the Paris pledges have the potential to reduce the probability of the highest levels of warming, and increase the probability of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius.

-

-

Global climate shift in the 1980s largest in 1,000 years

Planet Earth experienced a global climate shift in the late 1980s on an unprecedented scale, fueled by anthropogenic warming and a volcanic eruption, according to new research. Scientists say that a major step change, or “regime shift,” in the Earth’s biophysical systems, from the upper atmosphere to the depths of the ocean and from the Arctic to Antarctica, was centered around 1987. The scientists document a range of associated events caused by the shift, from a 60 percent increase in winter river flow into the Baltic Sea to a 400 percent increase in the average duration of wildfires in the Western United States. It also suggests that climate change is not a gradual process, but one subject to sudden increases, with the 1980s shift representing the largest in an estimated 1,000 years.

-

-

How bad will this El Niño be? Worse than you may think

Last week, Columbia University Earth Institute’s International Research Institute on Climate and Society convened a 2-day workshop reflecting on efforts over the past twenty years to improve responses to climate variability, especially risks associated with El Niño. Concerns that the current El Niño has the potential to exceed in severity the devastating El Niño of 1997-98 permeated the discussion. At the conference, Marc A. Levy of the Earth Institute presented a brief overview of the social, economic, and political changes that will have a large effect on human impacts from El Niño. He amplifies those remarks here.

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies