-

Ebola no longer a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”: WHO

On Tuesday the WHO officials met to consider the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa, and to decide whether the event continues to constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and whether the current Temporary Recommendations should be extended, rescinded, or revised. WHOconcluded that Ebola transmission in West Africa no longer constitutes an extraordinary event, that the risk of international spread is now low, and that countries currently have the capacity to respond rapidly to new virus emergences. Accordingly, the Ebola situation in West Africa no longer constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and the temporary recommendations adopted in response should now be terminated.

-

-

Ebola no longer a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”: WHO

On Tuesday the WHO officials met to consider the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa, and to decide whether the event continues to constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and whether the current Temporary Recommendations should be extended, rescinded, or revised. WHOconcluded that Ebola transmission in West Africa no longer constitutes an extraordinary event, that the risk of international spread is now low, and that countries currently have the capacity to respond rapidly to new virus emergences. Accordingly, the Ebola situation in West Africa no longer constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and the temporary recommendations adopted in response should now be terminated.

-

-

Sharing of research data, findings should be the norm in public health emergencies

Opting in to data sharing should be the default practice during public health emergencies, such as the recent Ebola epidemic, and barriers to sharing data and findings should be removed to ensure those responding to the emergency have the best available evidence at hand, experts say.

-

-

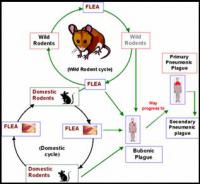

Identifying areas of plague risk in Western U.S.

Plague was first introduced into the United States in 1900, by rat–infested steamships which had sailed from affected areas. Epidemics occurred in port cities, with the last urban plague epidemic in the United States occurring in Los Angeles from 1924 through 1925. Researchers have identified and mapped areas of high probability of plague bacteria in the western United States. The findings may be used by public health agencies to aid in plague surveillance.

-

-

Flu season likely to peak in February

According to the CDC, seasonal influenza affects up to 20 percent of people in the United States and causes major economic impacts resulting from hospitalization and absenteeism. The flu season will likely peak in February in most parts of the United States, according to a model developed by scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Using historical data, a mathematical representation of how flu spreads through a population, and data for the current flu season provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the scientists were able to create a probabilistic model forecasting the flu season.

-

-

U.S. capability for treating Ebola outbreak sufficient but limited

The United States has sufficient capacity for treating another outbreak of the Ebola virus, but financial, staffing and resource challenges remain a hurdle for many hospitals and health systems attempting to maintain dedicated treatment centers for highly infectious diseases, according to new study.

-

-

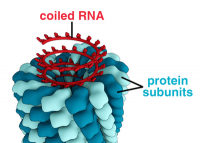

Plant virus to make Ebola detection more accurate

In the past, Ebola diagnostic tests, or assays, have been considered reliable only up to a point. The Ebola virus does not use DNA to store its genetic code. It uses a chemical cousin, called RNA, and extracted RNA degrades easily; one little mistake at the start of a test can ruin the whole thing. Novel process uses a plant virus and may ultimately make Ebola testing more accurate.

-

-

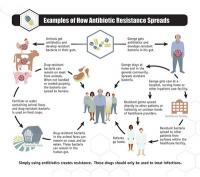

Rise of drug-resistant infections to cost millions of lives, trillions of dollars

Drug-resistant infections could kill an extra ten million people across the world every year by 2050 if these infections are not tackled. By this date they could also cost the world around $100 trillion in lost output: more than the size of the current world economy, and roughly equivalent to the world losing the output of the U.K. economy every year, for thirty-five years.

-

-

Study finds that Ebola vaccine is safe, stimulating strong immune responses

A clinical trial of a new Ebola vaccine that resulted from an unprecedented global consortium assembled at the behest of the World Health Organization (WHO) has found that it is well tolerated and stimulates strong immune responses in adults in Mali, West Africa and in the United States. If the vaccine is ultimately found to be safe and effective, it could offer crucial protection for contacts (family members, neighbors, etc.) of patients with confirmed Ebola disease in future epidemics, thereby helping to interrupt transmission. Larger trials of the vaccine sponsored, by GSK Biologicals, have already begun.

-

-

How infectious diseases become epidemics

Researchers are exploring how diseases spread across long distances in an effort to learn how better to control the next human, animal, or plant epidemic. The researchers will study data for vector-borne infectious diseases to model how these types of epidemics spread. Vector-borne diseases are spread by infectious microbes transmitted by ticks, mosquitos, or other insects or parasites.

-

-

Novel statistical model maps lethal route of Ebola outbreak

The traditional method to track disease spread is contract tracing, in which health workers interview patients and everyone they came into contact with. Contact tracing, however, is highly labor intensive. Using a novel statistical model, a research team mapped the spread of the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, providing the most detailed picture to date on how and where the disease spread and identifying two critical opportunities to control the epidemic. The result matches with details known about the early phase of the Ebola outbreak, suggesting the real-time value of the new method to health authorities as they plan interventions to contain future outbreaks, and not just of Ebola.

-

-

Oregon teen infected with bubonic plague

Health authorities in Crook County, Oregon, confirmed that a teenage girl has contracted bubonic plague from a flea while on a hunting trip. The girl became sick five days after the trip started on 16 October; and was rushed to a hospital in Bend, Oregon on 24 October.

-

-

Centralized leadership, major reform needed to bolster U.S. biodefense

A comprehensive report on U.S. biodefense efforts calls for major reforms to strengthen America’s ability to confront intentionally introduced, accidentally released, and naturally occurring biological threats. The report details U.S. vulnerability to bioterrorism and deadly outbreaks and emphasizes the need to transform the way the U.S. government is organized to confront these threats. Recommendations include centralizing leadership in the Office of the Vice President; establishing a White House Biodefense Coordination Council; strengthening state, local, territorial, and tribal capabilities; and promoting innovation through sustained biodefense prioritization and funding.

-

-

Missouri schools underprepared for pandemics, bioterrorism, natural disasters

Pandemic preparedness is not only critical because of the threat of a future pandemic or an outbreak of an emerging infectious disease, but also because school preparedness for all types of disasters, including biological events, is mandated by the U.S. Department of Education. Missouri schools are no more prepared to respond to pandemics, natural disasters, and bioterrorism attacks than they were in 2011, according to a new study. Particular gaps were found in bioterrorism readiness — less than 10 percent of schools have a foodservice biosecurity plan and only 1.5 percent address the psychological needs that accompany a bioterrorism attack.

-

-

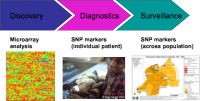

Surveillance technology to aid in disease detection, response

The Ebola crisis has highlighted a need to bolster global surveillance and enhance the capability to react appropriately to further outbreaks, experts say. This should include making use of modern technologies for detecting disease, sharing information in real time and analyzing data. “We cannot afford to wait for the next outbreak of infectious disease before putting effective systems in place to safeguard public health,” says one expert.

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies