Climate conundrumU.S. scientists to speak out on climate change

About half of the new Republican members of Congress are climate change skeptics, and 86 percent of them oppose any climate change legislation that would boost government revenue; many U.S. scientists are joining an effort to speak out on climate change, while other scientists express discomfort with blurring the line between science and policy-making

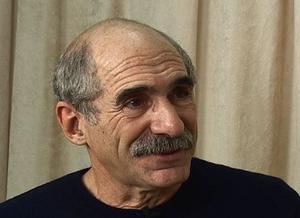

Princeton University's Dr. Michael Oppenheimer // Source: channels.com

Hundreds of U.S. scientists are joining a mass effort to speak out on climate change, experts said last Monday after skeptics gained political ground with mid-terms Republican gains in Congress.

The moves signals a bold approach by scientists, typically reluctant to get involved in policy debates, as President Barack Obama’s efforts to set stricter penalties for polluters face near-certain defeat in the legislature.

AFP reports that scientists involved insisted the mobilization was not in direct response to conservative gains in power and did not aim to influence public policy, but would offer the opportunity to present the facts when needed.

“I think it is important for scientists to assure that the public and policy makers have a clear view of what scientific findings are and what the implications of those findings are,” said Princeton University scientist Michael Oppenheimer. “To the extent that some members of the new majority in the House have exhibited a contrarianism to science, I think it is a good way to have a scientific community there to help keep its facts clear.”

One group of about forty scientists has been mobilized as a “rapid response team” to dive into the often hostile media environment and try to correct misinformation about global warming, said organizer John Abraham. “We did not form this to take a stance against climate change skeptics. However if a skeptical argument is put forward that doesn’t agree with science, we will refute that,” said Abraham, an associate professor at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Abraham said there was a wide gulf between what the majority of scientists accept as fact about climate change and what the American public believes. “This is in response to a real disconnect between what is known in the scientific community and the consensus among the general public,” he said. “Ninety-seven percent of top scientists are in agreement, but the public is split about 50-50.”

Indeed, a study by Yale University in October found that 50 percent of Americans know global warming is caused mainly by humans and just 19 percent understand that carbon dioxide can linger for thousands of years after it is emitted.

Another group convened by the American Geophysical Union consists of about 700 scientists who were on call to answer climate science queries for reporters covering the 2009 UN conference on climate change in Copenhagen and plan to do so again.

“AGU has been working over the past year on how to provide this service once again in association with the upcoming UN Climate Change Conference in Cancun, Mexico,” which takes place 29 November - 10 December, the group said on its Web site.

AFP reports that big oil and coal companies invest millions of dollars each year lobbying Washington that strict regulations on polluters would slash jobs and cause energy prices to spike, vastly outspending environmental groups.

As many as half of the 100 new Republican members of Congress “deny the existence of man-made climate change” while 86 percent oppose any climate change legislation that would boost government revenue, according to a recent post on ThinkProgress, a blog by left-leaning think-tank the Center for American Progress.

Obama’s plan to pass a cap-and-trade bill to impose the first U.S. restrictions on carbon emissions blamed for global warming faced hearty opposition even in the previous Democratic-controlled Congress.

AFP notes that blurring the line between science and policy-making stirs unease among some scientists. Judith Curry, who chairs the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, said she has signed on to neither initiative. “Scientific disagreement on a subject as complex as climate change is going to go on forever, and it should. Disagreement sparks scientific progress,” she said.

“Trying to quell scientific disagreement because you are concerned about diminishing the political will to act on your preferred policy is bad for both the science and the policy.”

Curry argues science should be more transparent in the wake of last year’s release of thousands of so-called ClimateGate e-mails, in which scientists expressed their inability to explain what they described as a temporary slowdown in warming and discussed ways to counter the campaigns of climate change naysayers.

The e-mails, intercepted from scientists at Britain’s University of East Anglia, a top center for climate research, were seized upon by skeptics as evidence experts twisted data in order to dramatize global warming.