Whole body scanner may be part of the answer, but not all of it

Whole body scanners should provide the answer to security screening, but the human element – people get bored, distracted, and careless – will make them less than flawless; the future of screening is technology that reduces the possibility of human error to zero; there is also a need for passenger profiling that does not need to take into account the race or religion of the passenger

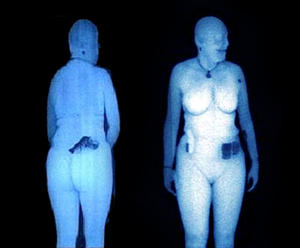

Whole-body scanner's image // Source: therawfeed.com

In the aftermath of the botched attack to blow up a Detroit-bound airliner on Christmas, the media and security analysts have seized upon full body scanners, or whole body imaging technology, as a solution to passenger screening problems.

Matthew Harwood writes that the controversial scanning technology, which allows security officials to peer underneath a passenger’s clothes, has seen a big push since the attack because 23-year-old jihadist Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab had sewn the high explosive he tried to detonate on the plane in his underwear — an innovation that eluded airport security in the Netherlands and Nigeria.

As former homeland security chief Michael Chertoff argued in the Washington Post, whole body scanners are one more critically important layer of security that can detect contraband metal detectors can’t. “Watch lists surely are an important layer, as is intelligence-sharing, but others, such as the deployment of advanced detection technology, are just as important,” he wrote (Harwood notes that Chertoff has a conflict-of-interest when promoting whole body imaging: One of the clients of his security and risk management firm is a manufacturer of whole body imaging technology).

Chris Yates, an aviation security analyst with Jane’s Information Group, wrote an article for BBC.com, reminding readers that these full body scanners, while certainly a “game changer,” are not “the panacea to the threats we face today.”

Why? Because of the human element. “Full body scanners are often only as good as the people paid to be behind the screens, analyzing the succession of complex images scrolling in front of their eyes,” he writes. “Staff monitoring screens typically only do so for a two-hour stretch - one of a rotation of duties to stop them from getting bored.”

Yates believes the future of screening is technology that reduces the possibility of human error to zero and discusses some emerging technology attempting to do just that. He also argues for passenger profiling that does not need to take into account the race or religion of the passenger.

The aviation industry routinely collects vast amounts of data on our traveling habits that can be used to build up an extremely useful profile. Information regarding the destination, frequency and duration of overseas trips allows those tasked with ensuring the security of flights to positively identify passengers who may travel to regions of the world determined to be high-risk for example. That enables higher levels of security to be applied to that person as he or she passes through the airport.

In the end, Yates argues for a smart blend of the best detection technology and the best profiling techniques to sniff out those that target the commercial aviation sector.