Water desalinationNew material enables more efficient desalination

Engineers have found an energy-efficient material for removing salt from seawater. The material, a nanometer-thick sheet of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) riddled with tiny holes called nanopores, is specially designed to let high volumes of water through but keep salt and other contaminates out, a process called desalination.

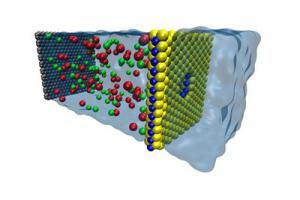

Computer model of a nanopore in a sheet of molybdenum disulfide // Source: illinois.edu

University of Illinois engineers have found an energy-efficient material for removing salt from seawater that could provide a rebuttal to poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lament, “Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink.”

The material, a nanometer-thick sheet of molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) riddled with tiny holes called nanopores, is specially designed to let high volumes of water through but keep salt and other contaminates out, a process called desalination. U. of I. reports that in a study published in the journal Nature Communications, the Illinois team modeled various thin-film membranes and found that MoS2 showed the greatest efficiency, filtering through up to 70 percent more water than graphene membranes.

“Even though we have a lot of water on this planet, there is very little that is drinkable,” said study leader Narayana Aluru, a U. of I. professor of mechanical science and engineering. “If we could find a low-cost, efficient way to purify sea water, we would be making good strides in solving the water crisis.

“Finding materials for efficient desalination has been a big issue, and I think this work lays the foundation for next-generation materials. These materials are efficient in terms of energy usage and fouling, which are issues that have plagued desalination technology for a long time,” said Aluru, who also is affiliated with the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the U. of I.

Most available desalination technologies rely on a process called reverse osmosis to push seawater through a thin plastic membrane to make fresh water. The membrane has holes in it small enough to not let salt or dirt through, but large enough to let water through. They are very good at filtering out salt, but yield only a trickle of fresh water. Although thin to the eye, these membranes are still relatively thick for filtering on the molecular level, so a lot of pressure has to be applied to push the water through.

“Reverse osmosis is a very expensive process,” Aluru said. “It’s very energy intensive. A lot of power is required to do this process, and it’s not very efficient. In addition, the membranes fail because of clogging. So we’d like to make it cheaper and make the membranes more efficient so they don’t fail as often. We also don’t want to have to use a lot of pressure to get a high flow rate of water.”