Water securityManaging the endangered Rio Grande River across the U.S.-Mexico border

The Rio Grande (called Rio Bravo in Mexico) is the lifeline to an expansive desert in the southwest United States and northern Mexico. From Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico, over 3,000 km, people depend on the river to quench their thirst and irrigate their crops. Yet as the river flows from the United States, it brings with it conflicts and challenges. The water level in the river is declining as use exceeds supply. Water demand is rising as the population in the region grows, and corresponding economic growth drives continued development. Moreover, climate change is expected to lower water levels even further, exacerbating the problems.

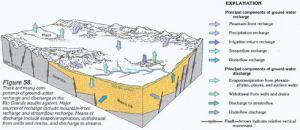

Streamflow in the Rio Grande and its tributaries is strongly affected by the altitude of the ground water in the basin fill near the river // Source: usgs.gov

The Rio Grande (called Rio Bravo in Mexico) is the lifeline to an expansive desert in the southwest United States and northern Mexico. From Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico, over 3,000 km, people depend on the river to quench their thirst and irrigate their crops. The river also forms the boundary between the United States and Mexico for 2,034 km.

Yet as the river flows from the United States, along the border, and into Mexico, it brings with it conflicts and challenges. The water level in the river is declining as use exceeds supply — an unsustainable situation. Water demand is rising as the population in the region grows, and corresponding economic growth drives continued development. At the same time, water pollution imperils and stresses the delicate ecosystems supported by the river. Ecosystems are often the last to be considered when water levels are low. Moreover, climate change is expected to lower water levels even further, exacerbating the problems.

IIASA notes that water allocation between the two countries is governed by the 1944 Treaty between the United States of America and the United Mexican States relating to the utilization of the waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers, and of the Rio Grande. The treaty was made at a time when the water resources were plentiful in relation to the population, and the environment was not yet something that policymakers considered at all. The new studysuggests that in order to preserve the river for the future, the involved parties can take advantage of an existing binational mechanism that allows flexibility to adapt the treaty without changing its structure. The study elaborates on four policy recommendations on how to do this.

Everyone wants to preserve their water supply, even when there is not enough water,” explains Luzma Fabiola Nava, a postdoctoral fellow in the IIASA water program and the author of the new study published in the journal Water.“The water supply isn’t enough anymore to meet the increasing demands. If we don’t allow for flexibility in the treaty, all these problems are going to get worse.”