Nuclear mattersGoal of eliminating HEU reactors faces hurdles

To lessen the risk of terrorists getting their hands on bomb-grade materials, the U.S. has led an effort to end the use of highly enriched uranium (HEU) in research reactors around the world; 72 HEU reactors have been modified or shuttered, but various government and academic facilities still operate around 130 HEU reactors — and these operators are reluctant to switch because of the complexities involved in changing to a new technology

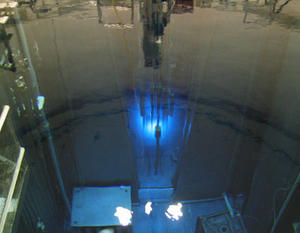

HEU reactor at Texas A&M University // Source: abcnews.go.com

A U.S.-led effort to end the use of highly enriched uranium (HEU) in research reactors around the world has prompted a lukewarm response from nuclear facility managers concerned by the complexities of changing to technology employing material that could not as easily fuel a bomb, Nature reported Monday.

The U.S. Global Threat Reduction Initiative has modified or shuttered seventy-two research reactors that once ran on highly enriched uranium; various government and academic facilities still maintain around 130 HEU reactors (Geoff Brumfiel, “Non-proliferation: A nuclear exchange,” Nature,11 October). The initiative “has partnered with dozens of countries worldwide … to convert research reactors to operate with [low-enriched uranium] fuel while maintaining their ability to complete their vital mission objectives,” U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) principal deputy administrator Kenneth Baker said Tuesday, according to released remarks (U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration release, 12 October).

Global Security News Wire reports that most recently, the U.S. program helped repatriate 1,000 pounds of Soviet-origin highly enriched uranium from a research reactor outside Warsaw, Poland.

The fear is that rogue actors could obtain nuclear-weapon material from HEU reactors. “Many of these places have very minimal security, said Matthew Bunn, a principal investigator at Harvard University’s Project on Managing the Atom.

Modifying such sites to run on lower-enriched uranium, however, is a slow, expensive, and complex process, according to Nature. In addition, HEU reactors can operate longer than their converted counterparts and use less fuel to release neutrons that aid in sustaining nuclear reactions.

“We are not so happy to convert our reactor,” says Grzegorz Krzysztoszek, who heads the Polish site.

Many organizations lack the millions of dollars they would need to convert their HEU reactors, or to buy the specially developed low-enriched uranium blend suited for use in modified systems. Scientists at U.S. government laboratories could soon certify another low-enriched fuel blend intended for use in reactors that cannot operate on LEU fuel now available.

David Moncton, who manages a research reactor for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, expressed frustration with the reactor conversion process. “We’re not running a reactor just to run a reactor. We do things with it,” he said.

Global Security News notes that despite reservations shared by some nuclear facility operators, the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration is planning a $3 billion, four-year effort to convert as many HEU research reactors as it can to use low-enriched fuel. “It’s an aggressive schedule,” senior GTRI official Andrew Bieniawski said of the effort, which would dovetail with President Obama’s goal of securing all loose nuclear material in the world within four years. “But I do think we can make it” (Brumfiel, Nature).

The National Nuclear Security Administration and the Russian state-run atomic energy firm Rosatom in 2010 “will finalize the legal framework that will allow us to begin studies to determine the feasibility of converting six research reactors inside Russia to operate with LEU fuel,” Baker said.

“In addition, NNSA and Rosatom have made great strides this year in working with international partners to return Russian-origin HEU fresh and spent fuel to Russia. To date, NNSA and Rosatom have cooperated to repatriate over 1,300 kilograms of Russian-origin HEU, enough material for fifty nuclear weapons. Currently we are in the midst of our most intensive campaign of shipments ever,” Baker said (NNSA release).

Still, Russia has “been very resistant” to altering its own use of HEU reactors, Bunn said. Roughly 60 reactors in the country were still running on weapon-grade fuel (Brumfiel, Nature).