Nuclear wasteTiny helpers: Atom-thick flakes help clean up radioactive waste, fracking sites

Graphene oxide has a remarkable ability quickly to remove radioactive material from contaminated water. Researchers determined that microscopic, atom-thick flakes of graphene oxide bind quickly to natural and human-made radionuclides and condense them into solids. The discovery could be a boon in the cleanup of contaminated sites like the Fukushima nuclear plants, and it could also cut the cost of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) for oil and gas recovery and help reboot American mining of rare earth metals.

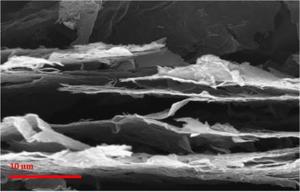

SEM image of graphene oxide flakes // Source: isna.ir

Graphene oxide has a remarkable ability quickly to remove radioactive material from contaminated water, researchers at Rice University and Lomonosov Moscow State University have found.

A collaborative effort by the Rice lab of chemist James Tour and the Moscow lab of chemist Stepan Kalmykov determined that microscopic, atom-thick flakes of graphene oxide bind quickly to natural and human-made radionuclides and condense them into solids. A Rice University release reports that the flakes are soluble in liquids and easily produced in bulk.

The experimental results were reported in the Royal Society of Chemistry journal Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics.

The discovery, Tour said, could be a boon in the cleanup of contaminated sites like the Fukushima nuclear plants damaged by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. It could also cut the cost of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) for oil and gas recovery and help reboot American mining of rare earth metals, he said.

Graphene oxide’s large surface area defines its capacity to adsorb toxins, Kalmykov said. “So the high retention properties are not surprising to us,” he said. “What is astonishing is the very fast kinetics of sorption, which is key.”

“In the probabilistic world of chemical reactions, where scarce stuff (low concentrations) infrequently bumps into something with which it can react, there is a greater likelihood that the ‘magic’ will happen with graphene oxide than with a big old hunk of bentonite,” said Steven Winston, a former vice president of

Lockheed Martin and Parsons Engineering and an expert in nuclear power and remediation who is working with the researchers. “In short, fast is good.”

Determining how fast was the object of experiments by the Kalmykov group. The lab tested graphene oxide synthesized at Rice with simulated nuclear wastes containing uranium, plutonium and substances like sodium and calcium that could negatively affect their adsorption. Even so, graphene oxide proved far better than the bentonite clays and granulated activated carbon commonly used in nuclear cleanup.

Graphene oxide introduced to simulated wastes coagulated within minutes, quickly clumping the worst toxins, Kalmykov said. The process worked across a range of pH values.

“To see Stepan’s amazement at how well this worked was a good confirmation,” Tour said. He noted that the collaboration took root when Alexander Slesarev, a graduate student in his group, and Anna Yu. Romanchuk, a graduate student in Kalmykov’s group, met at a conference several years ago.

The release notes that the researchers focused on removing radioactive isotopes of the actinides