-

Infectious outbreaks must be combatted strategically: Experts

New funding is not enough to guarantee success against emerging infectious diseases around the world. Rather, good governance, a long-term technology investment strategy, and strong product management skills are essential. As momentum builds for an international effort to develop drugs and vaccines for emerging infectious diseases, experts examine U.S. biodefense programs to understand approaches that might work and developed a global strategy for countermeasure development.

-

-

Resistance-proof antiviral can treat many diseases

Scientists and health officials are marshalling forces to fight Zika, the latest in a string of recent outbreaks. Many of these efforts target that virus specifically, but some researchers are looking for a broader approach. The new strategy aims to fight a wide range of viruses that appears to be safe in vivo and could evade a virus’s ability to develop resistance.

-

-

Efficient alternative for Ebola screening program for travelers

As of 31 January 2016, a total of 28,639 cases and 11,316 deaths have been attributed to Ebola, figures that are assumed to significantly underestimate the actual scope of the 2014 Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever outbreak in West Africa. In the United States, there were also two imported cases and two locally acquired cases reported in September-October 2014. Researchers offer an alternative policy for Ebola entry screening at airports in the United States. “Security measures implemented after 9/11 taught us a lot about what not to do,” one of the researchers say. “We learned that finding the one person who intends to do harm out of several million passengers is akin to finding a needle in a haystack.”

-

-

Ebola no longer a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”: WHO

On Tuesday the WHO officials met to consider the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa, and to decide whether the event continues to constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and whether the current Temporary Recommendations should be extended, rescinded, or revised. WHOconcluded that Ebola transmission in West Africa no longer constitutes an extraordinary event, that the risk of international spread is now low, and that countries currently have the capacity to respond rapidly to new virus emergences. Accordingly, the Ebola situation in West Africa no longer constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and the temporary recommendations adopted in response should now be terminated.

-

-

Ebola no longer a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”: WHO

On Tuesday the WHO officials met to consider the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa, and to decide whether the event continues to constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and whether the current Temporary Recommendations should be extended, rescinded, or revised. WHOconcluded that Ebola transmission in West Africa no longer constitutes an extraordinary event, that the risk of international spread is now low, and that countries currently have the capacity to respond rapidly to new virus emergences. Accordingly, the Ebola situation in West Africa no longer constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and the temporary recommendations adopted in response should now be terminated.

-

-

Protecting soldiers from emerging infectious diseases

Emerging infectious diseases that the U.S. military could encounter around the globe, particularly those found in tropical settings such as dengue, Burkholderia melioidosis, and malaria, are often difficult to distinguish by their clinical characteristics alone. Scientists from the Naval Health Research Center (NHRC) and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) held a two-day meeting earlier this month to discuss progress and goals for a joint biosurveillance project which aims to develop novel point of need (PON) diagnostics to identify pathogens that cause acute febrile illnesses and threaten global and public health.

-

-

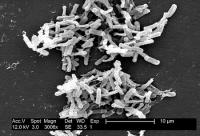

New test for infectious disease promises quick diagnosis

Researchers have come up with a way for inventing molecule probes quickly to identify deadly bacterial strains of infectious disease. The test can be done in less than an hour, compared to the current forty-eight hours, allowing for rapid, more accurate treatment of patients.

-

-

Scientists create malaria-blocking mosquitoes

Using a groundbreaking gene editing technique, scientists have created a strain of mosquitoes capable of rapidly introducing malaria-blocking genes into a mosquito population through its progeny, ultimately eliminating the insects’ ability to transmit the disease to humans. The technique holds the promise of eradicating a disease that sickens millions annually.

-

-

How infectious diseases become epidemics

Researchers are exploring how diseases spread across long distances in an effort to learn how better to control the next human, animal, or plant epidemic. The researchers will study data for vector-borne infectious diseases to model how these types of epidemics spread. Vector-borne diseases are spread by infectious microbes transmitted by ticks, mosquitos, or other insects or parasites.

-

-

Novel statistical model maps lethal route of Ebola outbreak

The traditional method to track disease spread is contract tracing, in which health workers interview patients and everyone they came into contact with. Contact tracing, however, is highly labor intensive. Using a novel statistical model, a research team mapped the spread of the 2014-15 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, providing the most detailed picture to date on how and where the disease spread and identifying two critical opportunities to control the epidemic. The result matches with details known about the early phase of the Ebola outbreak, suggesting the real-time value of the new method to health authorities as they plan interventions to contain future outbreaks, and not just of Ebola.

-

-

Can America cope with a resurgence of tropical disease?

Having stamped out a number of tropical diseases — including malaria — decades ago, is America today complacent about a rising wave of infectious disease? It is the nature of these diseases — neglected diseases, diseases of poverty, call them what you like — that they can go unnoticed for years, chewing away at the health of individuals and communities. As poverty, geography, climate, and social factors combine to bring tropical diseases out of hiding once again in the U.S. South, physicians, politicians, and the general public have to take the warning signs seriously and recognize that the tools available for tackling tropical diseases are sorely lacking. Despite tremendous advances in other types of illness in recent decades, tropical medicine remains stubbornly stuck in the 1950s, leaving the United States as unprepared as low-income nations to treat any significant number of cases. With diseases like Chagas now known to be prevalent and transmissible within the United States, better awareness, better tests, and better treatments are all urgently required. Otherwise, the number of people affected and infected will only continue to rise as this perfect storm grows ever stronger.

-

-

New research aims to slow the spread of infectious diseases

Emerging pandemic disease outbreaks such as Ebola increasingly threaten global public health and world economies, scientists say. We can expect five such new diseases to emerge each year — and spread. The tropical disease dengue fever, for example, has made its way to Florida and Texas, seemingly to stay. The NSF’s Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases (EEID) program supports research aiming to help understanding of the underlying ecological and biological mechanisms behind human-induced environmental changes and the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. This year, the program has awarded eight new grants totaling $18 million.

-

-

Mobile phone data help track spread of infectious diseases

Tracking mobile phone data is often associated with privacy issues, but these vast datasets could be the key to understanding how infectious diseases are spread seasonally, according to a new study. Researchers used anonymous mobile phone records for more than fifteen million people to track the spread of rubella in Kenya and were able quantitatively to show for the first time that mobile phone data can predict seasonal disease patterns. Harnessing cellphone data in this way could help policymakers guide and evaluate health interventions like the timing of vaccinations and school closings, the researchers said. The researchers’ methodology also could apply to a number of seasonally transmitted diseases such as the flu and measles.

-

-

Highly sensitive test to detect and diagnose infectious disease, superbugs

Infectious diseases such as hepatitis C and some of the world’s deadliest superbugs — C. difficile and MRSA among them — could soon be detected much earlier by a unique diagnostic test, designed to easily and quickly identify dangerous pathogens. Researchers have developed a new way to detect the smallest traces of metabolites, proteins or fragments of DNA. In essence, the new method can pick up any compound that might signal the presence of infectious disease, be it respiratory or gastrointestinal.

-

-

CHIKV Challenge winners --- forecasting the spread of infectious diseases

The chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is quickly spreading through the Western Hemisphere; as of 15 May 2015, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) had tallied close to 1.4 million suspected cases and more than 33,000 confirmed cases since the virus’ first appearance in the Americas in December 2013. Spread by mosquitoes, chikungunya is rarely fatal but can cause debilitating joint and muscle pain, fever, nausea, fatigue and rash, and poses a growing public health and national security risk. Governments and health organizations could take more effective proactive steps to limit the spread of CHIKV if they had accurate forecasts of where and when it would appear. But such predictions for CHIKV and other emerging infectious diseases remain beyond the reach of current modeling capabilities. To accelerate the development of new infectious disease forecasting methods, DARPA launched its CHIKV Challenge competition last year.

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies