-

Limited global risk of Madagascar’s pneumonic plague epidemic

Mathematical models have proven the risk of the on-going pneumonic plague epidemic in Madagascar spreading elsewhere in the world is limited. The study also estimated the epidemic’s basic reproduction number, or the average number of secondary cases generated by a single primary case, at 1.73. The case fatality risk was 5.5 percent. This was the world’s first real-time study into the epidemiological dynamics of the largest ever pneumonic plague epidemic in the African nation.

-

-

Heading off the post-antibiotic age

Worldwide deaths from antibiotic-resistant bugs could rise more than tenfold by 2050 if steps aren’t taken to head off their spread. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, warned of the danger of a “post-antibiotic age,” tracing the spread of antibiotic resistance to rampant overprescribing, to the widespread use of the drugs to promote livestock growth, and to the relative trickle of new drugs being developed as possible replacements.

-

-

How plague attacks us – and how we should defend ourselves

The plague that is believed to have caused the Black Death still occasionally ravages populations, albeit to a much smaller extent than before. Now we know more about how the bacteria attack us. But how does the plague bacterium attack human beings, and how does the body defend against its constantly evolving attacks? New research on the bacterium is yielding new answers.

-

-

Sanitizers made of paper kill bacteria dead

Imagine wearing clothes with layers of paper that protect you from dangerous bacteria. Now you can: Researchers have invented an inexpensive, effective way to kill bacteria and sanitize surfaces with devices made of paper. The motivation for the invention was to create personal protective equipment that might contain the spread of infectious diseases, such as the devastating 2014 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa.

-

-

Differentiating viral and bacterial infections

MeMed, an Israeli company specializing in molecular immunology, informatics, clinical infectious diseases and in vitro diagnostics, last week announced it has been awarded a $9.2 million contract by DoD’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) to fund the completion of MeMed’s point-of-care platform for distinguishing bacterial from viral infections.

-

-

Monitoring the emergence of infectious diseases

Zoonotic diseases that pass from animal to human are an international public health problem regardless of location — being infected with Campylobacter from eating undercooked chicken in the U.K. is not uncommon, for example — but in lower-income countries the opportunities for such pathogens to enter the food chain are amplified.

-

-

Risk of Ross River Virus could be next global epidemic

Australia’s Ross River Virus (RRV) could be the next mosquito-borne global epidemic according to a new research. The virus has been thought to be restricted largely to Australia and Papua New Guinea where it is harbored by marsupial animals, specifically kangaroos and wallabies, and spread by mosquitoes. The research shows that the virus may have been circulating silently in the South Pacific ever since a large epidemic of more than 500,000 cases in 1979-80, thought to have been started by an infected Australian tourist who travelled to Fiji.

-

-

Contact tracing, targeted insecticide spraying can curb dengue outbreaks

Contact tracing — a process of identifying everyone who has come into contact with those infected by a particular disease — combined with targeted, indoor spraying of insecticide can greatly reduce the spread of the mosquito-borne dengue virus. The new approach of using contact tracing to identify houses for targeted insecticide spraying was between 86 and 96 percent effective in controlling dengue fever during the Cairns outbreak. By comparison, vaccines for the dengue virus are only 30 to 70 percent effective, depending on the type of virus — or serotype — involved.

-

-

Symptomless Ebola – questions need to be answered before the next outbreak

Scientists know that Ebola can cause anything from severe hemorrhagic fever to no symptoms at all (asymptomatic infections). What wasn’t known, until now, is the number of people who experienced asymptomatic infections during the 2013-2016 outbreak of Ebola in West Africa. While the new report of asymptomatic cases of Ebola virus infection is not unique, it does raise important questions that need to be answered. Over the last couple of years, governments and global public health agencies have increased resources to tackle these questions. Hopefully, we will be better equipped and prepared for the next outbreak.

-

-

People with Ebola may not always show symptoms

A research team determined that 25 percent of individuals in a Sierra Leone village were infected with the Ebola virus but had no symptoms, suggesting broader transmission of the virus than originally thought. These individuals had antibodies to the virus, suggesting they had been infected at one time — yet said they had had no symptoms during the time of active transmission in the village. Theresearch confirms previous suspicions that the Ebola virus does not uniformly cause severe disease, and that people may be infected without showing signs of illness.

-

-

During 2013-16 epidemic, Ebola adapted to better infect humans

By the end of the Ebola virus disease epidemic in 2016, more than 28,000 people had been infected with the virus, and more than 11,000 people died from Ebola virus disease. Researchers have identified mutations in Ebola virus that emerged during the 2013-2016 Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa that increased the ability of the virus to infect human cells. “It’s important to understand how these viruses evolve during outbreaks,” says one researcher. “By doing so, we will be better prepared should these viruses spill over to humans in the future.”

-

-

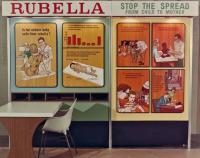

In Zika, echoes of U.S. rubella outbreak of 1964-65

Just over fifty years ago, a highly contagious but seemingly harmless virus swept through the United States, infecting as many as 12.5 million people. In both adults and children, the virus presented as a mild illness, but caused birth defects in some babies born to women who were infected while pregnant. Does this sound familiar? Though separated by time and place, there are surprising similarities in the social issues raised by the rubella outbreak of 1964-65 and the recent Zika outbreak in South America. Both viruses can cause birth defects, a fact that ties them to social issues surrounding pregnancy, women’s health, and the politics of abortion.

-

-

Biodefense Panel welcomes key provision in defense authorization bill

In October 2015, the Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense found that insufficient federal coordination on strategy, budgeting, and policy; inadequate collaboration with other levels of government and the private sector; and lagging innovation in areas like biosurveillance and medical countermeasure development make the United States vulnerable to biological attacks and infectious disease outbreaks. The Panel welcomed the passing by the House of the National Defense Authorization Act, H.R. 4909, which includes a provision addressing one of the Panel’s most important recommendations.

-

-

Bolstering international response capabilities to infectious disease threats

To make the world safer against future infectious disease threats, national health systems should be strengthened, the World Health Organization’s emergency and outbreak response activities should be consolidated and bolstered, and research and development should be enhanced, experts say

-

-

How will the next leader of WHO tackle future health emergencies?

In light of heavy criticism of the World Health Organization’s handling of the Ebola outbreak, the election process for the next director general will be under intense scrutiny. Experts outline the key questions on epidemic preparedness for prospective candidates.

-

- All

- Regional

- Water

- Biometrics

- Borders/Immig

- Business

- Cybersecurity

- Detection

- Disasters

- Government

- Infrastructure

- International

- Public health

- Public Safety

- Communication interoperabillity

- Emergency services

- Emergency medical services

- Fire

- First response

- IEDs

- Law Enforcement

- Law Enforcement Technology

- Military technology

- Nonlethal weapons

- Nuclear weapons

- Personal protection equipment

- Police

- Notification /alert systems

- Situational awareness

- Weapons systems

- Sci-Tech

- Sector Reports

- Surveillance

- Transportation

Advertising & Marketing: advertise@newswirepubs.com

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies

Editorial: editor@newswirepubs.com

General: info@newswirepubs.com

2010-2011 © News Wire Publications, LLC News Wire Publications, LLC

220 Old Country Road | Suite 200 | Mineola | New York | 11501

Permissions and Policies